A showdown in Mandalay on Friday will mark lethwei’s evolution from bareknuckle bouts in the Burmese countryside to a martial art studied across continents and broadcast through the biggest fight promotion in the world.

Dave “The Nomad” Leduc, the first foreign holder of a lethwei title, will face UFC veteran Seth Baczynski for the inaugural cruiserweight World Lethwei Championship (WLC) belt at Mandalar Thiri stadium.

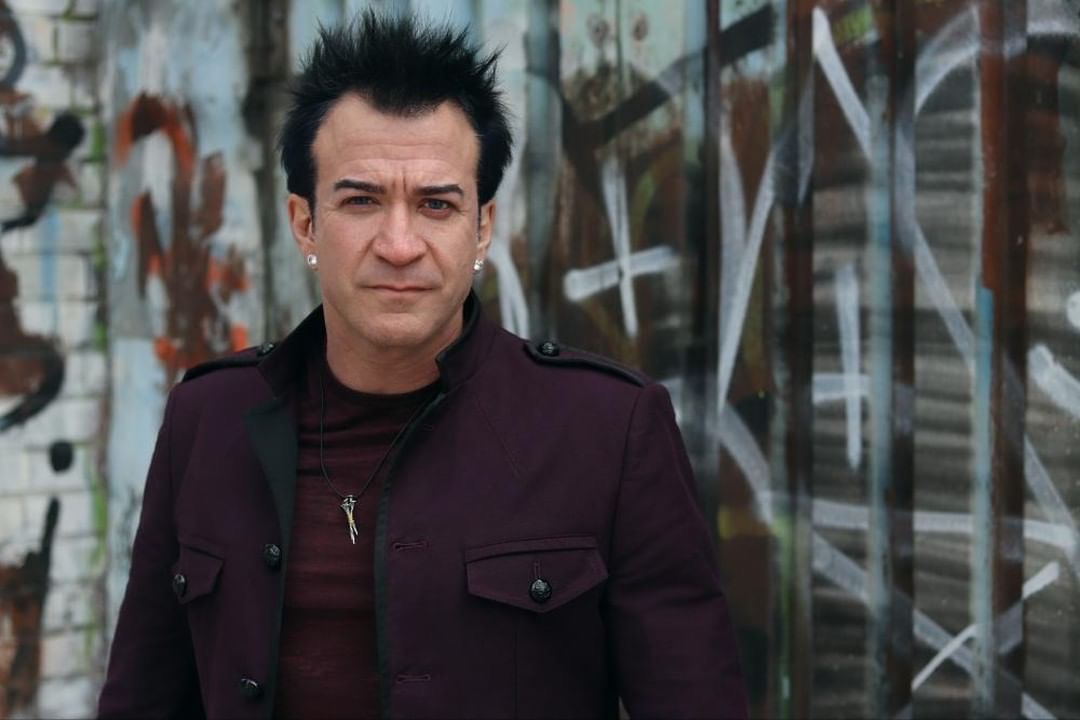

Shining a light on the match is Robin Black, a celebrated MMA analyst and colour commentator who has been displaying his new longyi on social media since landing in Myanmar two days ago.

Black first came to prominence as the lead singer of Canadian glam rock band Robin Black and the Intergalactic Rock Stars. Years of partying had him reconsidering his lifestyle—though not his love for adrenaline—so at the age of 36 he became a professional mixed martial artist.

His mission in Myanmar is to “peal back the layers and reveal the beauty underneath the brutality” of lethwei, he says, and his arrival comes at a stirring time for the country’s martial arts scene.

Kachin star Aung La N Sang reigns over the ONE Championship middle and lightweight divisions, ONE featherweight luminary Phoe Thaw is fostering a new generation of fighters in Yangon, and rising stars such as Bozhena Antoniyar and Tial Thang are coming off fresh victories.

With UFC Fight Pass and Canal+ in Myanmar streaming Friday’s event across the world, Black has seized the opportunity to share his love for lethwei.

One Minute #BREAKDOWN: the #art of the #HeadButt w/ The King of #Lethwei!@kingleduc #bink #KO!!

Lethwei is a #beautiful + violently artistic branch of the #MartialArts tree.

Enjoy The Hostilities.#myanmar @ufc @joerogan @danawhite @WorldLethwei @LethweiWorld @UFCFightPass pic.twitter.com/pKDP2nhxpD

— Robin Black (@robinblackmma) January 14, 2019

How is your trip going?

I love it here. The Burmese people are some of the most kindest and wonderful people I have ever met. I am immersed all day in a historic martial art and among incredibly talented ever-changing martial artists. I am exactly where I should be right now, and I couldn’t be happier.

When and how did you first encounter lethwei?

I’ve known of lethwei and martial arts from this part of the world since I was a child, but over the last decade, with the internet, and with the ability to film and share fights, I’ve become more aware of it.

The purity of lethwei is why it’s the ultimate striking art form. Dave Leduc and Gerald Ng, who runs the WLC, and a number of other people have made it more consumable and made people more aware of it.

It became possible for me to come be part of it, instead of watching it on the internet and thinking of it as this foreign, beautiful thing from the other side of the world. The world has shrunk and information has grown.

Though lethwei is being elevated to the global stage, descriptions of the sport often come with cautions of its brutality. How do you think an international audience will receive it?

As someone who deeply analyses martial arts, I view it as something different, as this emotional, psychological struggle between two trained but unwilling dance partners, each with two conflicting objectives, and in those moments are the secrets to the universe.

If you can figure out how to solve the pressure, stress and danger, and overcome yourself, you can take that knowledge and apply it to all things.

At the same time, I don’t want to suggest that it isn’t brutal; this is incredibly brutal and that’s part of its beauty. It takes a rare and special human being to enter a ring with another trained person who has the freedom you have in lethwei to physically express yourself.

In its brutally you find the beauty, elegance and inspiring nature of these super humans—no I take that back, normal humans who dare greatly to be special on the night. If you can’t see the incredible beauty in that you are simply not alive.

One Minute #BREAKDOWN: the Head #Bink in the Elegant Art of #Lethwei!

I am off to #Myanmar today to commentate the @WorldLethwei Championships Friday.

A true honour.Please join us Friday on @UFCFightPass.

And Enjoy The Hostilities My Friends.@kingleduc @ufc @joerogan pic.twitter.com/X9Wirdgje5— Robin Black (@robinblackmma) July 28, 2019

If you were competing in martial arts again, would you step into a lethwei ring?

I would. I would look at it as the highest request of myself. My wife would kill me.

My weakness when I fought, which has been revealed to me over the years as I analsye, was not being able to get the best of myself in those moments. I was able to sometimes, but other times I was not.

Now, over a decade and a half since I began the quest to fight, and now by studying the psychology and philosphy, how to overcome yourself and your fears, I understand that assignment.

The idea of being in a lethwei fight, half-naked, in an arena in Myanmar, is incredibly terrifying, but that’s precisely why I would want to do it, knowing full well the very real possiblity of disastrous failure.

We live in a world where a lot of us are scared to do anything because the fear of failure is so crippling to us. It’s precisely why we need to take risks, push ourselves and put ourselves in uncomfortable situations, because it is only through failure that your lessons are revealed and improvement can take place.

We live in a time where people view life as a spectator. People will be critical of each other as they sit in the stands of life writing tweets.

Back to your original question: I would do it. And the idea that my face could be carved open, and me laid out cold in epic failure in front of the world to make fun and judge me, is one good reason to get out of bed in the morning. To live a life where people dare greatly.

Can you draw any comparisons between the intimidation levels of performing in a huge concert and cage fighting?

Although I love performing, there’s no inherent risk of getting on stage, at least not enough risk to have that true feeling of exteme psychological arousal, when there’s an implied feeling of disaster or extreme success.

Dave Leduc was talking about the very real pressures and stresses of the leadup, and I said, ‘well, normal people don’t book a car accident for 8.30pm, Friday night August 2.’

And that’s what it is: a scheduled car accident, a violent confrontation with a professional athlete in your underpants in front of hundreds of thousands of people.

Every choice you make in the hours, days and weeks leading up to it are connected to that undeniable truth—that’s part of what makes it incredibly special, but also incredibly intimidating.

What’s your take on the main event?

There are so many fascinating dynamics. Seth is very much a ceberal and talented martial artist, but he’s also an Amercian football-type athelete, fast, strong, wiry—and that physicality contrasts massively with Dave, who probably doesn’t do any form of utra-specialised strength and conditioning.

His muscles, soft tissue, all would have been trained only through martial arts. Somebody would say, ‘we need to get a martial artist fit, let’s get them jumping, running, lifting weights.’ And a conflicting philosphy is that a martial artist becomes fittest for martial arts simply by training martial arts.

Compared to Seth, Dave is a specialist in the nine weapons [of lethwei: feet, knees, elbows, fists and head]. Seth is actually a further generalist, who trains eight of those weapons but also to wrestles, grapples, throws, trips.

I spoke to my friend [UFC fighter] Dominic Cruz about this match up…at a Bellator show. He said straight up to me, ‘I told Seth not to take this fight, this man is so much more of a specialist than him.’

In this particular art form, the specialist will find ways that are unfamiliar to Seth and then ruthlessly apply and reapply those approaches. That doesn’t mean Seth can’t defeat Dave; he 100 percent can.

Seth wants to be at the precise distance where Dave is on the end of his knuckles when he throws long punches. Dave will want to keep him pushed to the inside and pull him into the clinching range, where he can use his head and elbows.

Dave has so much more to lose as he becomes more successful. He needs to be free of that when he gets in there. Seth has got to travel to a beautiful part of the world and have an incredible experience immediately fighting for the chance to say he’s the best at a beautiful 2,000-year-old art form. That freedom is there for Seth. Dave has to free himself from the pressures of this fight and go out there and be in a state of violent play.

Double champ Aung La is regarded as the best fighter from Myanmar and one of the best in the world. How would he fare against his UFC counterparts Robert Whitaker and Jon Jones?

Aung La N Sang is a brilliant martial artist, a world champion with many great accompishments, but more importantly, he’s a wonderful, kind, generous, honourable human being.

In the short time I’ve been here, the Burmese people have been so kind that it doesn’t surprise me now that Aung La is the way he is. He’s a sort of extension of the Burmese people, a very special human being.

He can defeat any man. There’s not a human being on earth that Aung La N Sang could not beat in a fight—and that includes Jon Jones. He would defeat Robert Whitaker more often than not, and that’s taking into account that Robert Whitaker is an exceptional martial artist and has the ability to defeat him. Jon Jones would be a bigger challenge. He would need to be at his very best on the night, but if he is, he could absolutely defeat Jon Jones.

And do you have any advice for young martial artists in Myanmar?

The biggest key to becoming a good martial artist is the same key to becoming a master at anything: a constant dedication to tiny improvements, one after the other. As you make improvements, the improvements allow you to get better at making improvements.

You stack knowledge and make growth a habit. The two key things are persistence and patience. Have the persistence to keep going, part of that is being desperate for growth and improvement, but that is in conflict with patience.

It can’t all happen in a day, a week or a year. It will happen over a lifetime.

There is no destination. There’s only the journey and that’s the truth about martial arts or your relationship with your best friend or partner. That’s the truth about life. The process is the point. If you live that way, you are not in a rush, you go to work with as much honest dedication as you can today, and then go to bed, be proud of the work you have done, and wake up tomorrow with the potential to be even greater, if you live your life that way, you will achieve your goals.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.