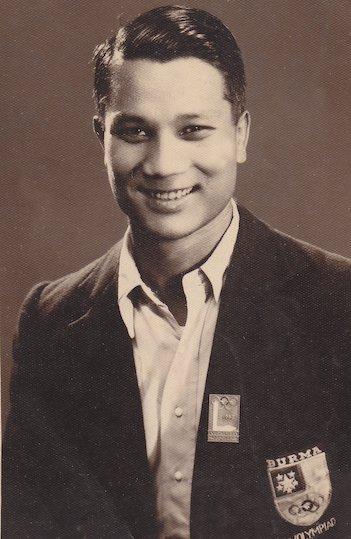

Like any martial art, the bare-knuckled sport of lethwei has its heroes. One of them is a Mandalay-born Olympian whose push to modernize the ancient art is one of the reasons why we see the odd flurry of lethwei strikes in Asia’s biggest MMA promotion, ONE Championship.

But Kyar “Tiger” Ba Nyein did not live to see the recent swell of interest in lethwei; the line of foreigners training in Muay Thai’s lesser known cousin, and the international media covering it.

In fact, he didn’t live to see the 1980s, but his passion for lethwei capped with his own sporting accomplishments have secured him a rich legacy in Myanmar.

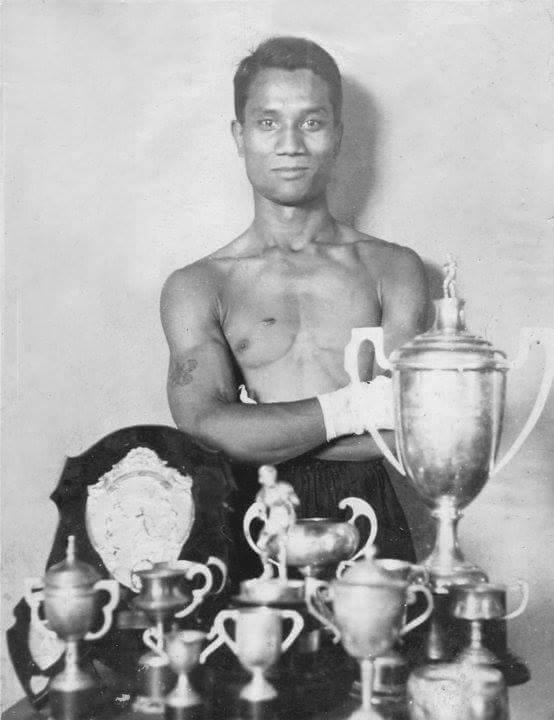

“Tiger” was born to a Muslim family in Mandalay in 1923, when the country was under British colonial rule. He learned Western boxing from a young age and won his first national trophy at the age of 13.

“For me, he is a great person, very technical and very humble,” said Win Zin Oo, 59, a former fighter and the owner of Thut-Ti, one of the most popular lethwei clubs in Yangon.

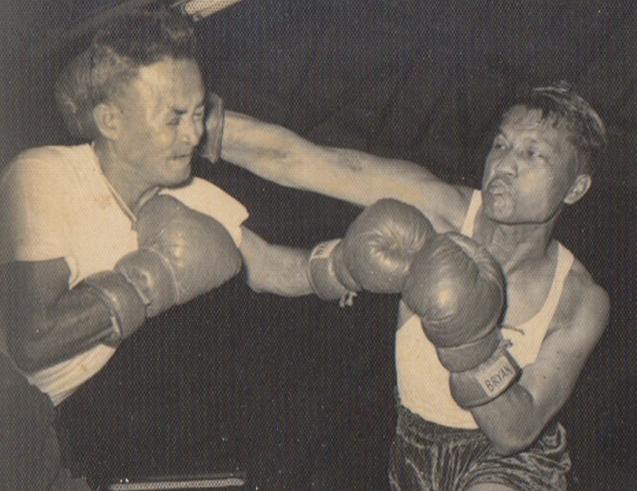

While Burma recovered from the carnage of World War Two, Kyar Ba Nyein sparred with Allied soldiers and earned his keep as a painter. During this time a police officer and locally celebrated boxer taught him how to maintain relentless pressure on his opponent, a strand of in-fighting that was to characterize his game.

He began competing internationally for Burma, collecting a string of victories that included Indian featherweight champion Benoy Bose, who twice competed at the Olympics.

This pivotal bout stood as the only Burmese win in the seven-match 1951 India-Burma tournament, spurring media to toast “Tiger” as the pride of the country. The following year he was picked to represent Burma at the Summer Olympics in Finland.

Unfortunately, he lost to a Polish boxer in the first round, but he returned to Mandalay and established Golden Tiger Boxing Club, which produced 10 national champions and trained street children for free.

Then in 1954 the athlete joined the government’s sports council as a trainer and launched his mission to revive lethwei, a provincial sport that, perhaps because of its associations with sandpits and loincloths, had become unfashionable with the country’s beau monde.

Whereas lethwei was previously win, lose or fail, “Tiger” introduced a 15 three-minute round system with each round sandwiched by three-minute breaks, creating the possibility of a draw.

“He gained a lot of respect from fighters, not because he was a rich man who could give money, but because he tried to introduce a system that bridged the traditional and international systems,” said Win Zin Oo.

“Tiger” travelled to the heartlands of lethwei near the eastern Thai border and chose fighters to train in the new system so they could compete in Yangon and Mandalay.

Though he retired from fighting in 1956, he continued to develop the scene and became a referee under the International Boxing Association. In 1960, he took about 100 fighters to Beijing and Shanghai in order to showcase lethwei.

Tiger was also a celebrated kyar-hto (Burmese draughts) player and wrote several articles and books on fighting, including his first work, Blood on the Sand. He translated a book on Muhammad Ali, becoming one of the first to introduce “The Greatest” to his country. He died on July 8, 1970 of colon cancer, but his legend in Myanmar was only just beginning.