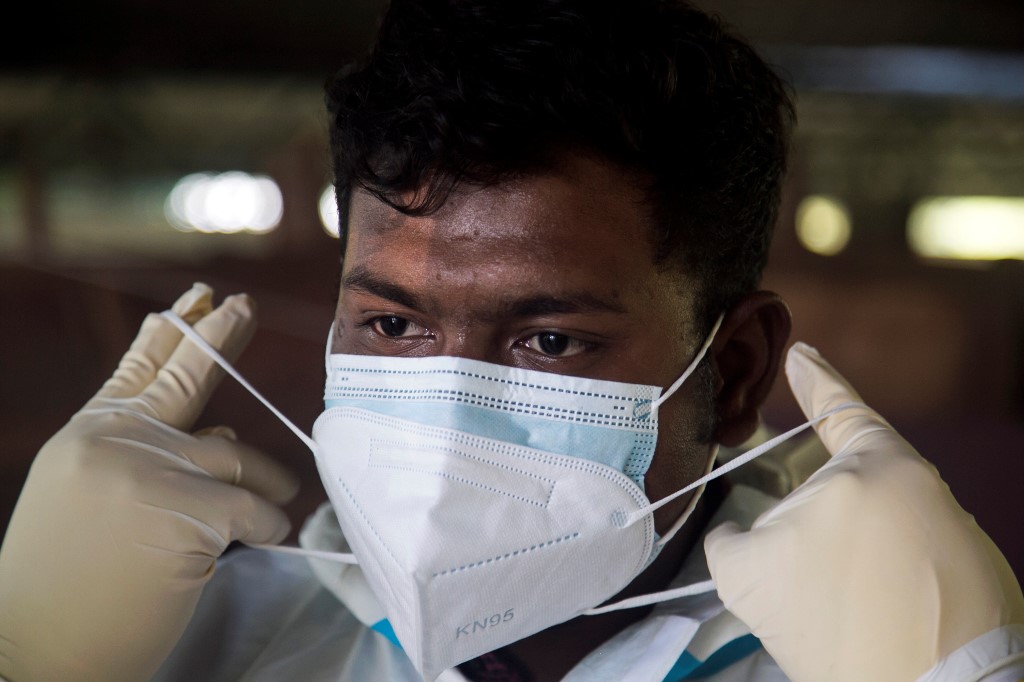

Sweating under his protective gear, volunteer Sithu Aung lays another coronavirus victim to rest—offering crucial funeral rites to his Muslim community in Myanmar's virus-ravaged commercial capital.

For the past few months, the 23-year-old father and his fellow volunteers have been living in a cemetery, isolated from their families, as they spend their days collecting the bodies of the deceased from Yangon's overflowing hospitals and quarantine centres.

Without the team's efforts, the bodies would be cremated—a practice that is usual in the majority-Buddhist nation but strictly forbidden under Islamic law.

Thanks to them, the dead instead receive a short funeral conducted by a local imam at a Muslim cemetery, in the presence of a handful of socially distanced immediate relatives.

"I get satisfaction from the happiness of their families and knowing that Allah sees what we're doing," former shopkeeper Sithu Aung tells AFP.

"That's why we're risking our lives to do this job."

Yangon's Muslim community numbers about 350,000—seven percent of the city's population—and various Muslim associations have provided the volunteers with three ambulances, two cars and supplies of food.

The stigma attached to the virus means renting an apartment to isolate from their families is not an option, so the team of 15 have commandeered shacks inside the cemetery compound.

Clad in full protective suits, rubber gloves, goggles and plastic face shields, they work shifts around the clock, beating a path through Yangon's traffic-choked streets with flashing emergency lights and sirens.

'Crying under our goggles'

For months, Myanmar remained relatively unscathed by the pandemic, registering fewer than 400 cases nationwide by mid-August.

But that all changed when case numbers started to surge in a country with one of the weakest healthcare systems in the world.

There are now over 100,000 infections, with more than 2,000 deaths.

Myanmar's teeming commercial hub Yangon became a virus hotspot and Sithu Aung's team now collects three or four bodies every day.

They work a rotational shift: two weeks on, then a week's self-isolation that allows Sithu Aung to spend a few days with his wife and one-year-old son before he returns to his macabre work.

When the city first went into lockdown in April, he chose not to tell his family about his plans to volunteer.

"If I'd have let them know, my mum and my wife wouldn't have let me do it," he admits, adding his family sometimes visit him at the cemetery, although they keep their distance.

Sithu Aung helped bury Myanmar's very first coronavirus victim, a 69-year-old Muslim man, and remembers his fear of touching the body.

After helping to bury dozens of coronavirus victims, however, he says he is no longer afraid of death.

But he admits the emotions can still be overwhelming.

"I feel sorry that family members can't see the faces of their loved ones," he says, soaked in sweat after peeling off layers of protective gear.

"Some days we also cry under our goggles."