"Among all the creatures and characters of Burma’s rich mythological tradition, the Zawgyi, a semi-immortal human shaman dressed in red, is perhaps the most well-known.

The Zawgyi seeks to create a philosopher’s stone that would free the possessor from old age and death, circumventing the cycle of birth and death (samsara), that the Buddha declared the fate of all living things.

Obsessed with a dream of change and transformation, hungry for eternal life and neverending youth, craving power and insight that this existence has failed to provide him, he walks the space between the worlds."

Aung Khant Moe, Burmese Mythological Tradition

"The study of alchemy and alteration is known in Burmese as Aggiya—the Work with Fire."

Donald M. Seekins, Historical Dictionary of Burma

THE CROWS are screaming overhead, but I can no longer see them. I am buried up to my neck, my body is encased in mud, and she is standing over me, her green eyes flashing. It ends where it began, in Kandawgyi Park, the stone returned at last to the heart of the Golden Land...

Where to start? With the city. Yangon; Myanmar’s grime-stained jewel, city of toothless smiles and ruptured pavements, feral dogs and puddles of red spit. A city that grows on you like the moss that blooms on every ramshackle wall, city of silent tragedy, of sunset prayer, the glowering remains of spent imperial majesty.

I had lived there for a few years, most of them alone—I could tell by the crow’s feet that bloomed at the edges of my eyes, the thin lines that spidered out when I pulled my face into a smile before my bathroom mirror. I smoked joints of imported bush weed, slipped in through the Bangladeshi border, sticks, seeds and stems spilling through the gaps in my fingers, mingling with the desiccated bodies of roaches that littered the parquet floor.

If I ventured out, it was with my camera around my neck. I made my money in the night, crouched in the corners of rooftop bars, capturing wealthy locals and foreigners inside the dark box of my camera. I caught them at their happiest, their most free, eyes like lighthouses, buzzed on Ritalin and martinis and youth, a hundred metres above the city’s streets, where humans slept like crumpled longyis in the doorways of dilapidated buildings. Later, I would watch them bloom again in the red light of my darkroom, dancing one final time, reanimated by bottles of foul-smelling chemicals, immortal, young and high forever.

That was the day that it changed. How could I have known that morning, cursing over coffee, wiping sweat from my forehead, that my life would never go back to the way it was? Or that my actions would drag the city into a darkness more terrible than any blackout? But I left for my walk in Kandawgyi as if this were any other day.

Kandawgyi Park feels as though it has existed forever, but this is an illusion. Like much of the city, it was created to serve the needs of the British colonial administration—one lake transformed into another. The lake is artificial—water channelled through a series of pipes from nearby Inya Lake. It was not enough to take the country—the British had to recast it in their own image.

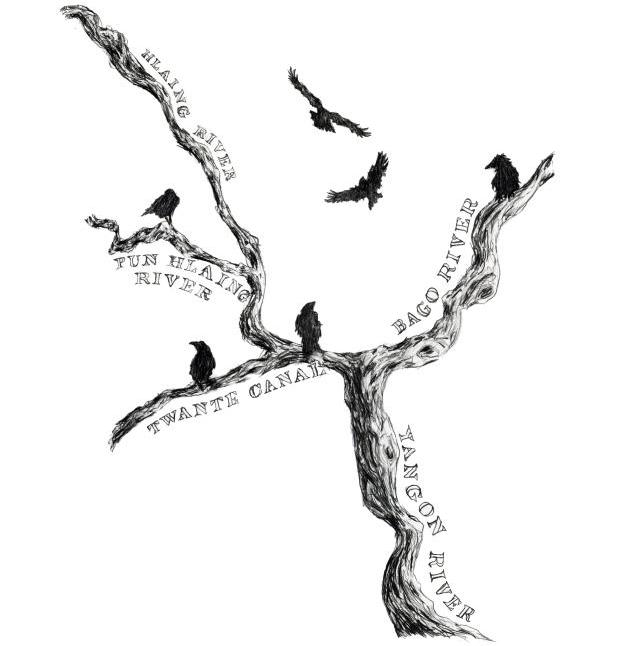

Kandawgyi would be a placid place, if not for the crows. After a day of scavenging, they take roost in the park’s many trees, turning them black and solid with their rustling bodies. In the evening, as the orange sun begins to set, you will see them—the flocks joining voices, taking flight in a single horde, screaming from above the lake, billowing, silhouetted by the setting sun. In those long evenings, I would watch them from a lakeside bar, marvelling at their unity, their connection, the way they moved with direction and purpose, before returning my gaze to the still waters of the lake or the emptied bottles of Myanmar beer in front of me, like the cityscape of the temple-city of Bagan, reaching eternally towards the sky.

But it was the morning then, and dead silent. I made my way t0 the perimeter of the park and started my walk—a spiral, narrowing as I approached the centre, where a temple-boat floated on the lake. I had always thought that the creature at the boat’s prow was a naga, a Burmese dragon-serpent, but read later that it was, in fact, a karaweik, a bird from some especially dark corner of Burmese legend.

I had walked that park a hundred times, and I knew the paths well. Occasionally, a red-faced foreign jogger, working hard before the day's heat set in, staggered by, but at this time the park was almost always empty, a rare break from the city’s thronged streets.

But that day was different.

First, I heard a man’s voice, drunkenly humming in an out-of-key baritone, with a gravelly edge of cigarettes and whiskey. Second, I smelled the spice of alcohol in the air. Finally, I saw him; facing away from me. If not for the humming, I would never have noticed—he was half-hidden in a short downward ridge, sprawled against a tree stump, his feet dangling in the water of Kandawgyi Lake.

I crept closer, my footsteps soft on the lush grass, and caught a view of him from up above.

He was a striking man. Tall for a Burmese, his sun-weathered face still displayed a handsome bone structure under the sagging skin. From where I stood, I could make out a bold black moustache, and a bristly beard jutting from his chin. In his right hand, he was holding what I took to be some kind of fishing pole, but on closer inspection was a walking stick, carved from dark and mottled wood.

Perhaps most strikingly, he was dressed all in red, although his clothes were dark and stained in places. Crimson trousers (looser than the western style), a faded red jacket, and a bright scarlet beanie, worn high up on his head, completed the outfit.

He seemed, as far as I could tell, to be deeply enjoying himself. He had taken off his jacket, which lay in a heap behind him, and was washing his feet in the water, humming as he did so.

I considered a quiet “mingalabar” but decided it was better to leave him be. As I watched, he took another long swig from the bottle of whiskey, then spat contently, with the impressive, phlegmatic sound god has gifted only Burmese men the ability to produce. I smelled betel nut in the air, the sharp scent of slaked lime, and briefly wondered if his teeth were a stained red that matched the rest of his attire.

I was about to move away when I saw it. His jacket was behind him, lying crumpled on the emerald grass. One pocket had fallen open slightly, and a strange, faint luminescence caught my eye. I looked more closely and saw an object, half-hidden by the fabric of his pocket. It was some kind of stone, about the size of an egg, but it gave off its own light, seeming to glow from within. For some reason, I could barely take my eyes from it, and I crept a step closer, being careful to keep my footsteps soft. And then I watched, like the viewer of a film projected on a distant screen, my right hand creep out and close around it.

Inside my palm, the stone felt warm and surprisingly heavy. I was taking care to be quiet, and the man's humming masked any sound I made. I realised that he was blind drunk, I could have cursed him at full volume and not distracted him from his lakeside soak. Before I knew what I was doing, I took a few slow steps back and slipped the stone into my pocket.

I crept off, moving back through the park until I reached the long bridge, where I started to jog, slowly at first. I gathered speed, and by the time I had reached the park’s perimeter I was almost running. As I did, I heard a cry go up—a sound of amazement and anger echoing across the waters of the lake. It rang out twice more, and the third time it was no longer the war-cry of a man enraged, but a trembling sound full of horror and impotence, animal and pitiful. I shuddered, even in the heat, and quickened my pace.

As I left the park and slipped back into the streets of Yangon, I felt overcome by guilt and shame. My heart was beating in my chest like a taiko drum, and sweat was pouring from my body. What had possessed me? For all I knew, the stolen item was of great value—Myanmar is the home of many precious gems. Or even forgetting money, perhaps it had been a family heirloom, a memento of youth, a gift, a lucky charm, and I had taken it without justification or reason. Dejected, I considered that I had added my name to a long list of plundering colonists, another foreign thief seeking to steal away the fire from the heart of the Golden Land.

I took a different route home. As I dodged taxis and stumbled over the cracks in the pavement, I felt the gaze of the omnipresent Burmese aunties, watching from laundry-strewn balconies over their respective kingdoms. I felt the shame of my guilty conscience, and the sensation mingled with their all-seeing eyes, which I felt like sunburn on my neck. I tried to walk upright, but if you had been a crow circling above, you would have seen me scuttling through Yangon’s streets like a roach.

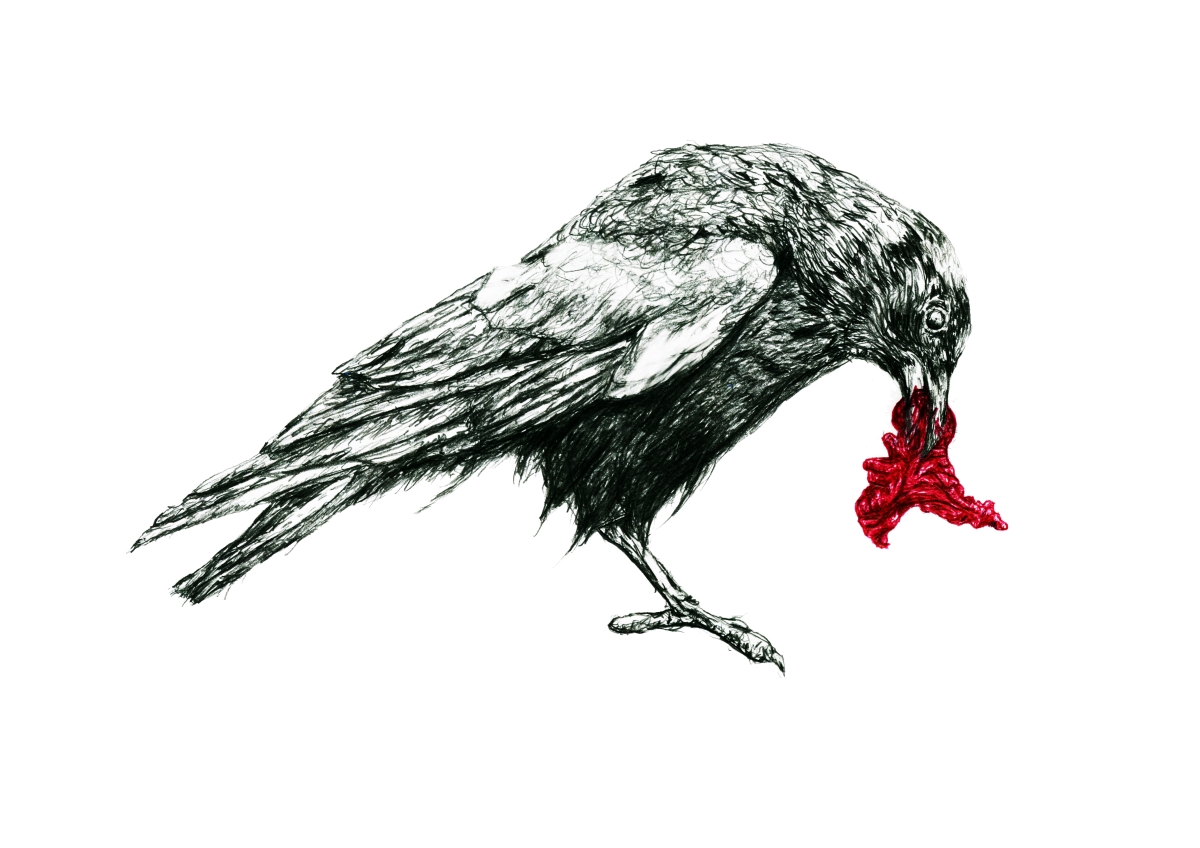

Yangon is a city of smells, a place where you can literally follow your nose, and at last, the scent of grilled halal chicken told me I had reached Bogolay Zay, the market street where I lived. The holes in the concrete revealed the chaos churning below, wafts of decay and sewage leaked through the stone. As I passed a side alley, I heard a croak and glanced to one side. A few metres away, a colossal crow stood perched on a dead rat, pale and bloated, the crow gripping its mangy fur. As I watched, the bird looked up at me, black eyes glittering like beetles, then plunged its gore-soaked beak into the rat’s distended belly, tearing out some mysterious rat-organ and tilting its head back to swallow it whole. I stood transfixed, watching the blood-slick beak dive in and out until another stab of anxiety propelled me to stumble the last few meters to the stairs leading to my home.

I half-ran up the staircase, and turned so rapidly onto my landing that I almost collided with someone. It was the girl who lived next door, who gave a surprised yelp as I almost ran through her.

“I’m sorry!” I exclaimed, wiping a patina of sweat from my forehead. She looked back at me with an expression of concern. She was carrying three transparent bags of noodles, soup and mohinga, and had almost spilt them on the floor.

“Please be careful!” she exclaimed, taking in my sweaty appearance. For the first time, I noticed her green eyes, which gazed fiercely out from between the two straight curtains of her black hair. I had seen her a few times before, and nodded a quiet greeting when I did see her, but this was the first time we had spoken.

“Are you OK?” she asked.

“Yes! Yes. Fine. Just uh, been for a run.”

Her eyes moved over my clothes—flip flops, a sweat-soaked grey t-shirt. I realised my hand was still in my pocket, fingers clasped over the stone’s surface.

“You run in flip flops?”

“Yes,” I said, mind racing. “To tan my, uh, feet.”

She gave me a long, searching look. I wondered how long it had been since I spoke to another person. I tried to think of something else to say.

“Well, anyway, uh. Enjoy your noodles.”

She clutched the noodles slightly closer, as though afraid I was about to try to snatch them from her. Then she smiled.

“Good luck with your tanning.”

I nodded maniacally and drew away, practically sprinting the last few metres to my apartment. As soon as the door closed behind me, I took a long breath before double-bolting it. With a beer from the fridge in my hand, and sitting comfortably on my bed, I pulled the stone out. The sun was streaming in through the large windows, and I held the stone up, letting the light play over its surface. The more I looked at it, the more complicated it seemed to be—there were purples and reds in its translucent heart, light shades of blue, obsidian blacks and a vivid, hypnotic green, like no colour I had ever seen before. I don’t know how much time passed there, with me staring at it, but I came to with a start, and slipped it into my pocket, turning it in my fingers like a rosary.

That night, I stashed the stone under my pillow before turning off the light. I barely slept—tossing and turning and caught in a torrent of uneasy dreams. I dreamt I flew over the twinkling lights of Yangon, over the monolithic Shwedagon Pagoda. On either side of me, hordes of crows flapped along, regarding me with amused indifference. I dreamt of something huge and buried, sleeping under the city, and of dark things stirring in the night.

Then the city slipped away from me, and I felt myself falling, through the land and the sea, into somewhere darker than I had ever thought possible. I dreamed of a dragon with three heads, one male and two female, and I dreamed of a tall man on a mountainside, picking bright red fruit with long and wizened fingers, humming a familiar song in his gravelly voice.

I dreamed of a hare that lived inside of the moon. I dreamed of the cold of the earth and wet mud pressing down on me, burying me alive. And finally, I dreamed of endless green, green fields, as far as the eye could see, and for some reason, this dream filled me with the most fear of all, and I woke drenched in sweat, clutching the stone, with terror grasping at my heart.