For our weekly top picks and freebies straight to your inbox, sign up here.

When anti-racism protests began rippling across the USA and beyond in late May, Myanmar activists saw an opening to challenge a long-used term that has accrued the stench of prejudice.

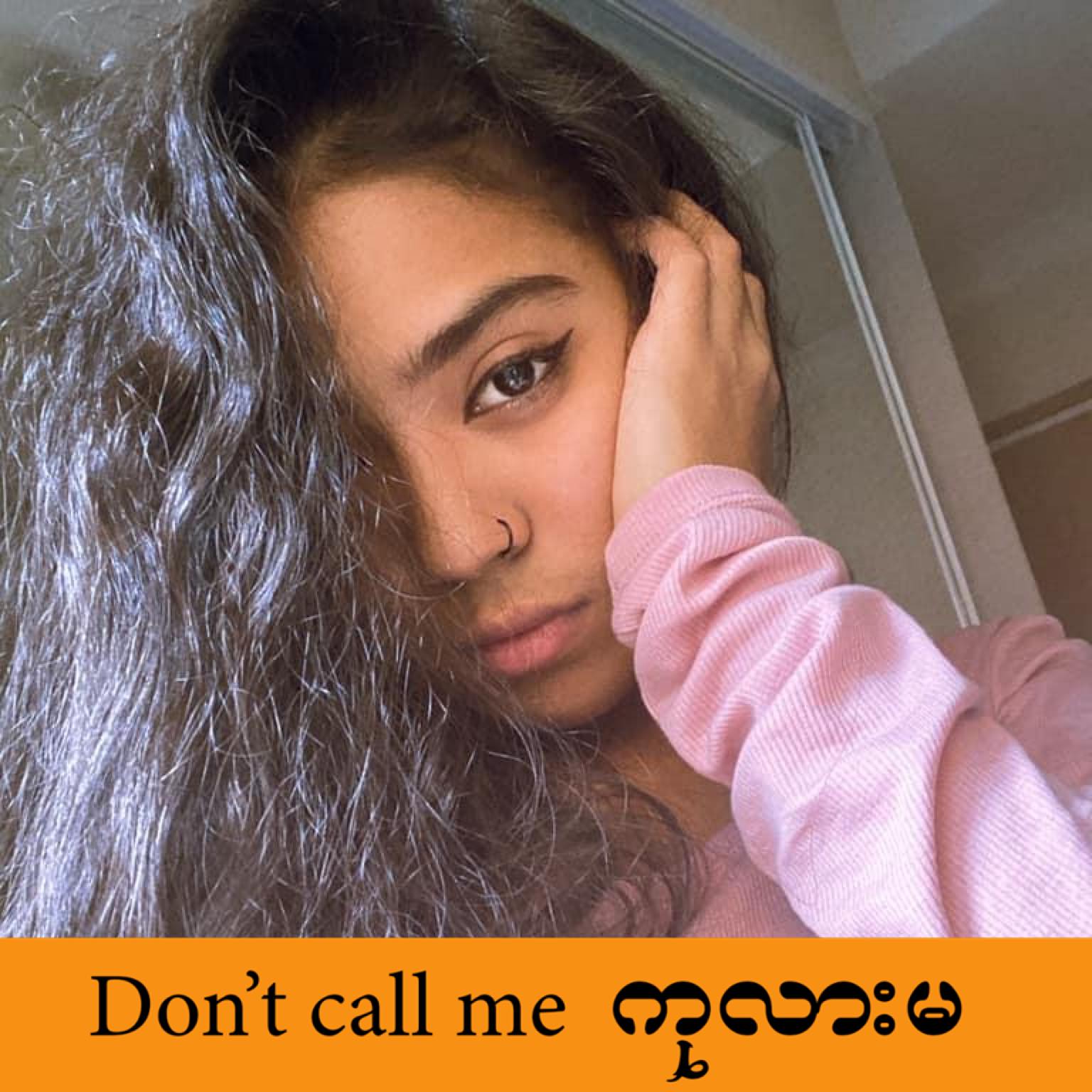

"Don't Call Me Kalar,” reads their campaign slogan, a rejection of a word that historically refers to people from the Indian subcontinent, but has increasingly become a contemptuous term for people with darker skin, intended to make them feel like outcasts in their own country.

The campaign has mostly fallen on deaf ears, say activists, who are accused of being oversensitive. Racial struggles should not be among Myanmar’s US imports, argue the larger opposition; far from a weapon of racial or religious discrimination, they say, the word is needed to describe everyday objects such as chairs and chickpeas. If anything, it is a term of endearment.

Health science student Daung Teza tweeted an explanation summarising the reluctance to stop using the label.

The unwillingness to stop using the k-word has to do with sustaining the myth of the Bamar nation. In this myth, people of Indian descent are perpetual guests that should be grateful to their hosts.

— Daung Teza (@daungteza) June 12, 2020

‘Traditional vocabulary’

Ko Ko Gyi, 58, a Bamar politician who has spent about two decades behind bars in the struggle for democracy, posted on Facebook on June 10 a couple of benign sentences that used the term. He mentioned spilling chickpea (kalar peh) curry, preparing mango pickle (tayat thee kalar deh) on a chair (kalar htine), reading an 18th century historian called U Kalar.

A prominent leader of the student protests in 1988 against junta rule, Ko Ko Gyi posted later that day that his family would teasingly call his mother “kalarma,” which accompanied a chorus of agreement from other Facebook users.

Darker skinned people were called the word as a “cute nickname used between good friends who adore each other,” posted one account, while another, who said his own nickname was “short fat,” added, “We even used to tease people who were normal.”

Ko Ko Gyi went on to write that marking the term as hate speech is “not beneficial to anyone and will lead to the opposite result.”

In the pursuit of equality, “the country should be in unison,” he said, working together “with citizens of different religions for the same result of political, economic, and societal gain.”

“I’ve personally never used this word as an insult,” he said. “I haven’t heard any cases of anyone using this word to insult and discriminate another person. Strive for equality, don’t cause problems about traditional vocabulary.”

But pursuing equality is the point of the campaign, according to one of its creators, Kashmir Kaur, 19, who has a Punjab, Shan, and Chinese heritage.

“I am saddened by Ko Ko Gyi’s reaction towards how young generations are striving at their best regarding racism and equality,” she told Myanmar Mix.

The use of the word has changed over the decades, said Kaur, who recalled the term being used against her in school, and more recently, when a car slowed down as she cycled with a friend.

“When they came closer to us, they shouted ridiculously ‘kalar ma tway ha (or Indian women)!’ Then they drove away laughing,” she said.

Bad experiences tied to the label have made her feel inferior to others, she said.

“People who say the word is not racist and try to normalise it are ignorant of how the intentions behind the word changed over time,” added Kaur. “Everybody’s got right to say if they like being called a particular term or not. After all, it’s all about mutual respect.”

Thet Zin, chief editor of The World Today, posted on Facebook on June 9 that he liked being called kalar while he was at university, although it is unclear whether he has Indian heritage.

“My brother, Min Zin, was called kalar by his friends as well. I’ve never seen him get offended or deny it,” he wrote.

Myanmar Mix reached out to him, however he declined to comment further.

On June 3, cartoonist Thant Myat Htoo gave his opinion in the form of comic strips along with a post that described the hashtag #CallingKalarIsRacism as a form of brainwashing inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement.

His cartoons depicted Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and Buddhists to highlight the different ways the word is used; sometimes as an insult, he said, and other times not. If we accept the word is racist, he said, more words will face the firing line and the cycle will never end.

Thant Myat Htoo then seemingly removed the post after a strong reaction from thousands of netizens. Some agreed with his message, while others criticised his depictions of minorities as stereotypical and demeaning.

‘Non-human kalar dogs’

The word has undeniably been embraced in racist vocabulary, as shown in a 2018 Reuters investigation into content attacking the Rohingya and other Muslims on Facebook.

Among the posts sampled were “non-human kalar dogs, the Bengalis, are killing and destroying our land” and “we must fight them the way Hitler did the Jews, damn kalars!”

Like most other countries, Myanmar is afflicted by racism; it runs through its bureaucracy and erects barriers to citizenship for minorities. Immigration officers are known to label Muslims “Bengali” on the pink-coloured Citizenship Scrutiny Cards and the Passport Issuing Office even has a slow-moving unmarked queue for those deemed to have “mixed blood” such as Sino-Burmese people.

The activists are not saying new words must be created for nouns that encompass the term, such as chair and chickpeas, said Kaur. Nor are they comparing the label to the way the N-word is used in the USA. But when the term is deployed to imply that a person is not one of Myanmar’s “national races” or taingyintha, that is discrimination, she said.

“I am looking forward to a time when the word is not used towards somebody based on their skin colour, religion, or ethnicity,” she added.