Min Sett Hein, 27, is a Myanmar filmmaker who has lived in the UK since he was a teenager. He joined a group of Myanmar expats who travelled to The Hague this week to support Aung San Suu Kyi.

The leader defended her state against allegations of genocide on Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine state at the International Criminal Court (ICJ). Here are the accusations and defence from the three-day hearing. And here’s Min Sett Hein’s account and photos.

Wednesday, December 11

I do not support either side in this case; I’m neutral. But when my cousin and his wife—Suu Kyi devotees—asked me to join them and their four-year-old son on their trip to the Netherlands, I couldn’t resist seeing what this big gathering of Myanmar people would be like. Needless to say, it was the weirdest family trip ever.

On leaving The Hague’s central train station we heard Burmese, Chin, and Kachin languages float past and saw people wearing traditional ethnic clothes.

A five-minute walk from the supporters was a counter protest where Karen, Rakhine, Chin and other minorities joined the Rohingya to protest against Suu Kyi and the Myanmar military. Some ethnicities had also joined the mainly Bamar group cheering Suu Kyi.

Among the roughly 350 supporters were families with children who had been raised in the west by parents fleeing Myanmar’s military regime. A local Dutch woman asked one of the children why he was there.

“Because my parents brought me here,” he replied.

Television presenter Maung Maung Aye had flown from Yangon to be here. Suu Kyi, or “Amay Suu” to him, was a godsend amid these challenging times for the country—he took warmth from the presence of a leader like her to defend Myanmar, he told me.

At lunch, those with cars brought rice with chicken curry and fried fish.

Another supporter, Sonny Aung Than Oo, had been living in Europe for 30 years. “She needs our support now more than ever,” he said. “Which is why I came, despite being ill. I am here until December 13, I heard there’s an opportunity to meet her on that day.”

Indeed, Sonny was correct: Suu Kyi would greet her fans on Friday—and also on Thursday, when I would meet her.

Some supporters sympathised with Suu Kyi, who, aged 74, should be enjoying a quieter life, said supporter Thin Thin Shwe.

“She’s going there, defending a case that wasn’t even her responsibility, for us and her country,” she said.

Among the crowd, a Dutch woman holding a sign reading “without justice there is no peace” said the case was simple.

“Any action that causes a million people to flee, you are committing a crime against humanity. Whether you commit genocide is technical legal analysis, and it’s pretty obvious it ticks the box,” she said.

Later, two Muslim women came over to the Suu Kyi rally—perhaps mistaking it for the Rohingya rally. Another woman walked over and asked the two women to cry in front of her camera. The pair did not seem to understand English and replied in German before wandering off. It was a strange moment.

Thursday, December 12

I spent the night at the house of my host family—incredibly generous people who had moved from a refugee camp in Thailand to the Netherlands. Although they didn't know us, the husband and wife, who work in a local swimming pool, would not let us spend a penny.

I walked in front of the ICJ where about 150 fewer Suu Kyi supporters had gathered that morning. Two people began reciting their poems for Suu Kyi through megaphones.

The group erupted when they saw her car and started singing the Myanmar national anthem after she walked into the building.

Everyone took group photos outside the court as I warmed my hands; it was much colder than the previous day.

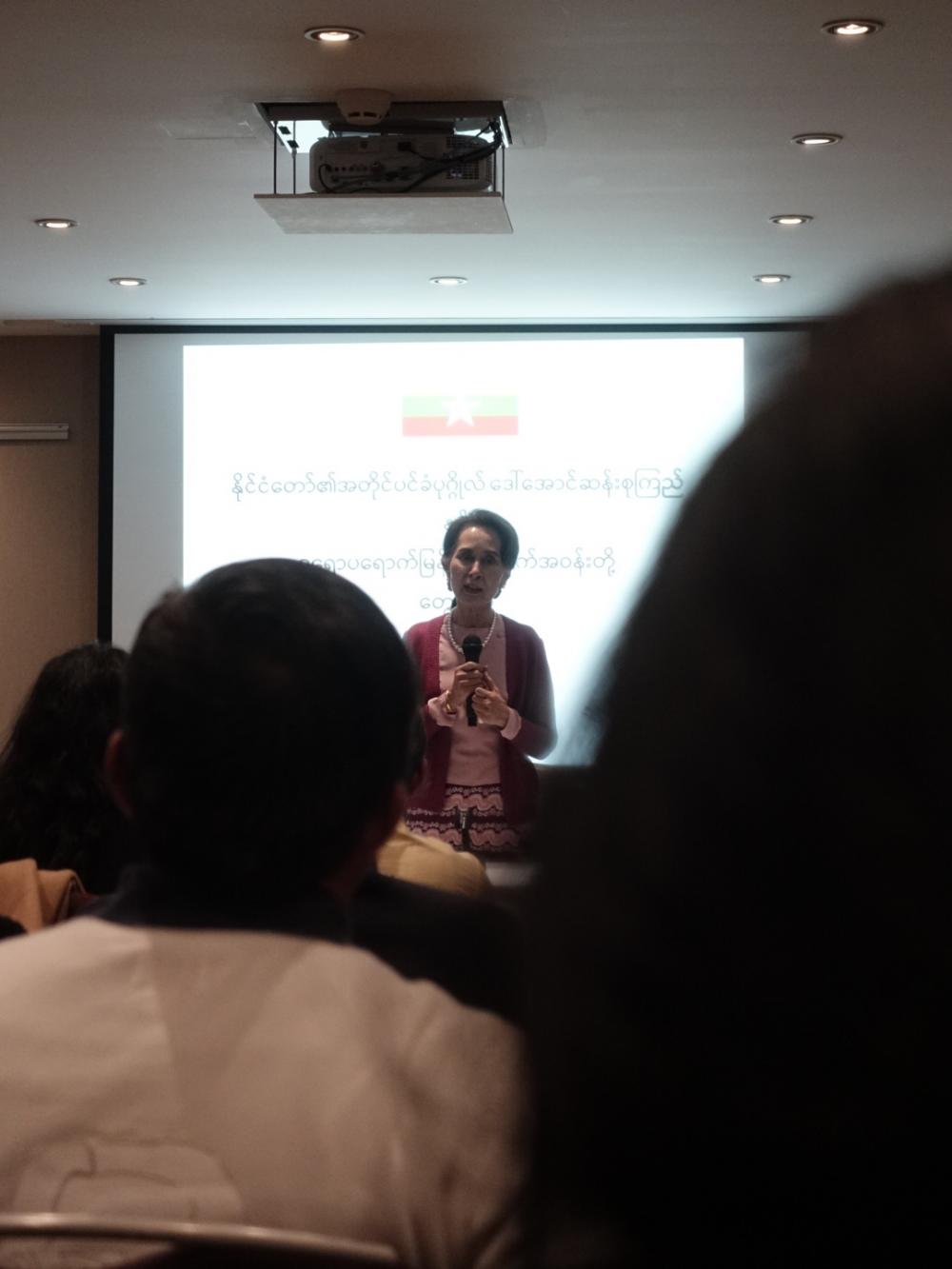

We had been told Suu Kyi would meet us at her hotel, The Hilton, in The Hague that evening. No phones, no live streaming, no selfies, no questions about the case.

At about 6.30pm, we packed into one of the hotel’s meeting rooms, where supporters told her how thrilled they were to see her and that they had prayed for her health. She seemed happy and said some words of encouragement.

"For a country to develop, what's important is the people's mindset. Some might say Myanmar people are divided but that's not true—we're only like that when we have arguments sometimes,” she said, joking.

“When we face something, we face it together hand-in-hand. That's something unlike anything else. It's almost like we're reminding each other. I came here to face this issue, but facing it together as a whole makes it all bearable."

She had also arranged to meet more supporters the next morning, but by then I had left The Hague, back to my job in London.

Ultimately the rally felt more like a chance for Myanmar nationals living abroad to come together—albeit for a “great cause” in the form of supporting their leader.

The military junta had made some of their lives hell, and here they were, supporting a leader who was defending the institution that had caused them so much pain. But their devotion to Suu Kyi rose above anything else.