“Do you want some of these fried noodles?” asked a woman as I took a photo of her family on a picnic blanket during last week’s Yangon Pride in Thakhin Mya Park.

They had come prepared for the six-hour event, carrying lunchboxes, drinks, and power banks to charge their phones so that they could document their kids running around.

Even though I wanted the noodles, I politely declined and asked if they were waiting to see one of the day’s big draws, award-winning actress and singer Htun Eaindra Bo—Myanmar’s original diva.

“We’re waiting for everyone,” she responded.

Pride in Yangon is a tricky thing. How do you create a safe space where the queer community can celebrate without causing backlash? And that comes from not only conservatives who feel threatened by the LGBTIQ community but also LGBTIQ people who want to cater to everybody’s needs.

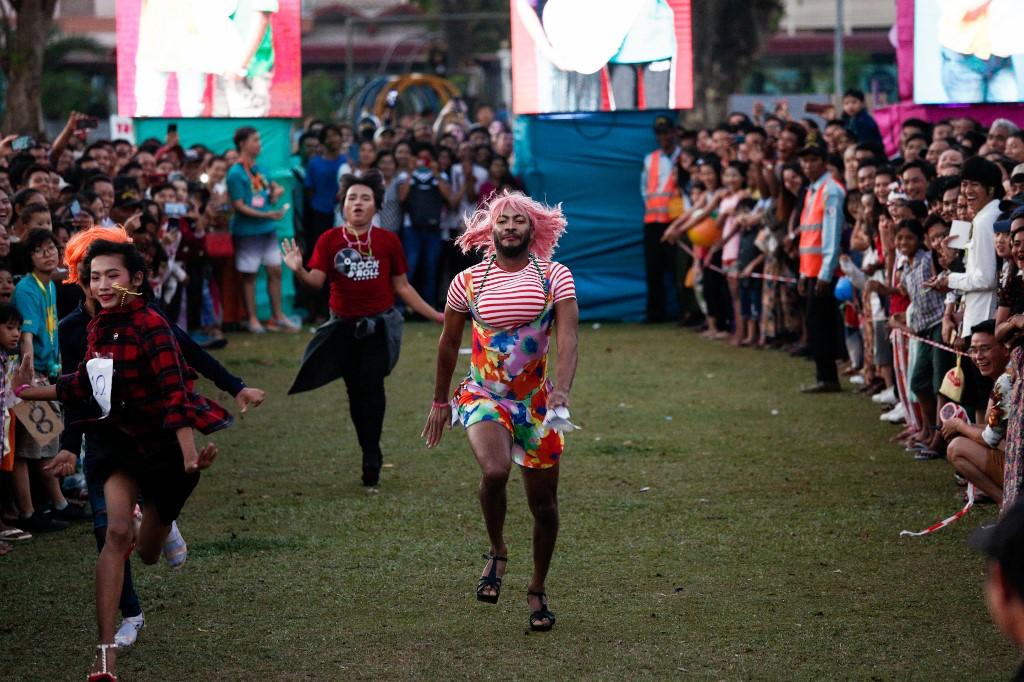

But I can see Yangon Pride people really doing their best to push for inclusivity. The boat parade that kicked off Pride was probably the party of the year so far. Rainbows, happy faces, flirty conversations, drunken dancing friends, observational sober folks. General warmth and acceptance. A sense of family.

People had long debated the need for Pride, saying it is unnecessary, an excuse to party. In some countries, secure heterosexuals want a Straight Pride of their own despite it being Straight Pride the moment they leave their homes.

In Yangon, Pride does not include a march because that could be considered as protest. It is also a long and complicated process to get permission for. But, as apparent by the last two years, Yangon Pride is only getting stronger and better every time.

Richie Htet’s sold-out exhibition titled “A Chauk” is possibly the first solo exhibition by a gay man about the queer experience. Yin Phwint Yar, the first LGBTIQ hotline in Myanmar, also launched around the time of Pride, and the Love Is Not A Crime campaign turned out to be the occasion’s biggest publicity draw.

Profile frames with a pink pinky flooded newsfeeds on Facebook and people were dipping their pinky fingers in pink paint to show their support for the LGBTIQ community. With wide media coverage, the campaign could be a major boost for legal reform as we approach the 2020 elections in November. As it stands, being queer is still illegal in the country.

Yangon Pride is not just a “party” event; it hosted multiple workshops focused on legal reform and mental health. LGBTIQ films from Myanmar and beyond were screened. The campaign videos featuring LGBTIQ members and their accepting family and friends radiated a much-needed warmth and positivity for LGBTIQ representation in media. A performance art piece about queer bodies and desire was also a special highlight.

People are starting to realize the importance of accurate representation. More than 15,000 people attended the Pride events this year, said the organisers.

After a night of very queer performances with drag kings and queens and Htun Eaindra Bo, I ran into the woman who offered me fried noodles. What did she think of everything? She loved it all.

“Do you know what this event is for?” I asked.

“Of course,” she said. “My oldest niece is a lesbian. Very tomboy-ish. I actually just sent her this photo.”

She showed me a printed photo from the Love Is Not A Crime booth. She and her family, including the kids, were all smiles, raising their pink pinkies. And this is why Pride is important.