World War Two saw a highly unusual British general carry out two major military operations inside Japanese-occupied Burma.

Major General Orde Charles Wingate was killed in an air crash in the Chin Hills during the second operation, on 24 March 1944, this closing the career of a soldier as colourful as he was controversial. He was aged just 41, yet had almost 15 years of campaigning already, beginning with hunting poachers in East Africa with the Sudan Defence Force in the late 1920s.

This was followed by two years as a captain on the intelligence staff in Palestine, during the Arab insurgency of 1936-39, where, at the behest of the British military commander, General Archibald Wavell, he formed specialist units combining British soldiers with volunteers from the Jewish police, aimed at using the insurgents’ own methods—ambush, surprise night attacks on hostile villages—against them.

These Special Night Squads were in some ways the forerunners of modern special forces and Wingate was revered for many years as one of the founding fathers of the Israel Defence Forces, as his Night Squads included Moishe Dayan and Yigal Alon, both legendary commanders of the IDF from the 1940s to the 1960s and both counting Wingate as their mentor.

Wingate was a fanatical Zionist who sometimes shocked even David Ben Gurion with the vehemence of his beliefs and extended his support eventually to personally lobbying British government ministers, something which would normally be career suicide for a serving British Army captain and it may have been the outbreak of the Second World War which saved him.

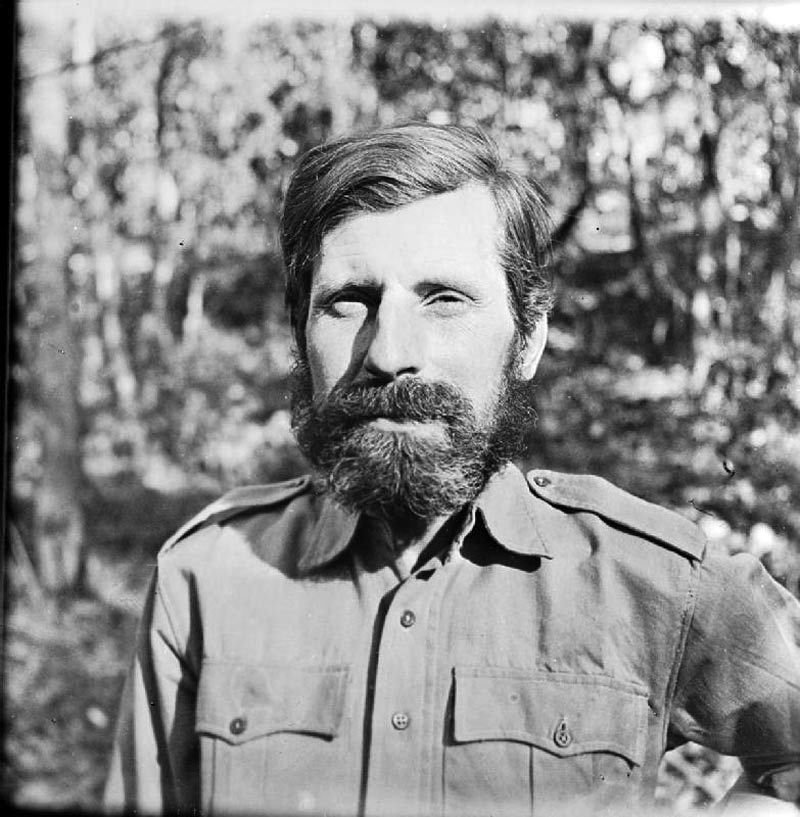

Indeed, he is remembered as much for his behaviour as for his military exploits—he ate six raw onions a day, and expected all his officers to eat at least one, gave press conferences in the nude while scrubbing himself with a wire brush and often carried an alarm clock to remind others that ‘time was passing.’ Although a strikingly handsome man—with a beautiful, far younger wife, as intelligent and strong in her beliefs as he was—he was given to wearing scruffy, crumpled uniforms on campaign, along with a solar topee helmet and thick beard.

Despite all this, when Italy declared war on the British Empire in June 1940, Wingate’s name was soon put forward to lead guerrilla operations inside Ethiopia, which had been invaded and occupied by the Italians in 1935-36. He entered Ethiopia in December 1940 at the head of Gideon Force, a mixture of Ethiopian refugee soldiers and Sudanese professionals commanded by British officers; perhaps more importantly, he had with him Haile Selassie, the exiled Emperor of Ethiopia.

By spring 1941, Wingate had defeated the Italian garrison of the western Ethiopian province of Gojjam, a force at least six times the size of his, and ridden at the head of the procession which brought Haile Selassie back into his capital, Addis Ababa, on a horse intended originally for Mussolini. Wingate was seriously ill with cerebral malaria by the end of the operation and afterwards overdosed on mepacrine, becoming delirious and trying to cut his own throat in a hotel room in Cairo.

This confirmed the view many of Wingate’s detractors had of him as mad. Fortunately, his theatre commander in East Africa was again General Wavell, who now became his saviour. When the Japanese invaded Southeast Asia in early 1942, Wavell was British Commander in Chief in the Far East, and it was he who requested Wingate—now back in full health—to initiate operations inside Japanese-occupied Burma similar to those in Ethiopia.

In response to this, Wingate formed the Long Range Penetration Groups, or, as they are better known in Britain, the Chindits, a word based on Wingate’s own mispronunciation of Chinthe, he seeing a flying spirit which guarded pagodas as a good inspiration for a force operating in Burma by land and air.

Wingate intended Chindit forces to penetrate deep behind Japanese lines in the hills of northern Burma to attack supply bases, supply routes and airfields so as to not only threaten Japanese logistics, but, more importantly, divert Japanese troops and attention away from the Burma-India frontier and weaken their forces facing the main British armies there. To do this, they were trained intensely in jungle warfare and did not have any vehicles, relying on mules to carry their equipment over the mountains and parachute drops for resupply.

The first Chindit Force was 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and it was perhaps not ideal for the kind of operations Wingate envisaged, containing two infantry battalions, one of them British and full of conscripts over ideal military age, the other an inexperienced Gurkha battalion with many teenaged boys; however, alongside these was the Burma Rifles, mainly Chin and Kachin tribesmen led by British and Burmese officers and able to pass on their valuable skills and experience to others.

Wingate commanded this force on Operation Longcloth, from February to May 1943, which saw him take 77th Brigade across the Chindwin into northern Burma to attack the railway from Mandalay to Myitkyina, which they cut in over 70 places as well as killing large numbers of Japanese in ambushes, with Wingate’s ideas on air resupply vindicated—partially. However, the Brigade lost 1,000 of its 3,000 men, some of them Burma Riflemen who stayed behind to wage guerrilla war against the Japanese, the rest either killed or captured while the others withdrew to India at the end of the operation.

Nevertheless, Longcloth had a massive positive impact on British morale in Asia, as a British force had successfully taken on the apparently invincible Japanese in the jungle and had given them major trouble, albeit at a cost. One such impressed was the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who invited Wingate to the Allied conference in Quebec, where he met President Roosevelt and the US Chiefs of Staff, who were also highly impressed—enough to offer Wingate the necessary force and materials for a far larger operation.

This was Operation Thursday, of March-June 1944, which saw a 20,000-strong Chindit force delivered by American gliders and aircraft to bases across a large swathe of northern Burma with the aim of supporting the advance of the US-Chinese Army, under the American General Joe Stillwell, from India to reopen the ‘Burma Road’ across northern Burma and with it, a land route to America’s ally, Nationalist China.

However, a new objective emerged almost as the Chindits were flying in, as this coincided with the Japanese launching their offensive against Imphal and Kohima, Wingate diverting part of his force— against orders—to attack the rear of Japanese forces carrying out the offensive. How effective all this was is debated to this day, but Thursday did see an entire Japanese division, of 8-10,000 men, destroyed, along with an estimated 500 Japanese aircraft and forces which might have swung the balance at Imphal diverted to deal with the Chindits.

This, then, might have been Wingate’s greatest victory, but sadly he did not live to see it.