Travel writer James Fable, 25, spent two years living in Myanmar, where he gained some memorable experiences at Chin state’s heart-shaped Rih Lake, the rugged mountains of Nagaland, and other spectacular destinations in the country.

In this extract from his newly-released debut book, In Search of Myanmar: Travels Through a Changing Land, illustrated by Chuu Wai Nyein, the UK native visits a Yangon palmist with his girlfriend to discover what his upcoming journey holds in store. However, the palmist seems more interested in James' love life than in his travelling fortunes, creating an awkward atmosphere for everyone there.

Visit the writer’s website here.

Chapter 1: Prophecies and Plans

The rain was crashing down in sheets as we stood beside the grimy green garage, waiting for our man. Shwe Ei put her hands together in prayer and briefly looked towards the golden pagoda glimmering through the monsoon gloom. Then she turned to me and smiled. Shwe Ei (‘Soft Gold’) had dark gold skin, full lips, rich hazel eyes, and flowing black hair that many girls would envy. She wore a silver and purple ingyi (a short-sleeved blouse) with a matching longyi (a looped sarong). It had been her idea to see the palmist. A white jalopy pulled into the drive and out jumped a jolly man clutching a laptop case. He gave us each a nod and lifted the garage door, revealing a white-walled office with a floor covered in water. A modest desk sat opposite a dusty bookshelf bent on collapse; framed certificates for astrology, palmistry and fortune-telling littered the walls.

“Sar-pi-pi-la?” asked Shwe Ei. ‘Have you already eaten?’ is the traditional Myanmar greeting – possibly coined because food used to be scarce, though nobody really knows.

“Sar-pi-pi” (‘I have eaten’), said the palmist as he sat down at his desk. He unzipped the black laptop case, extracted a grey brick and turned it on. Windows ’98 hummed into action. Shwe Ei went to see this palmist roughly every six months; her mother sought his advice monthly. I, however, could not decide whether his appearance inspired confidence or warranted despair: his grubby shirt was tucked into an elegant black longyi with cream stripes while thick rectangular lenses magnified his brown eyes to popping point. Patchy hair barely concealed a discoloured scalp, and beneath his crooked nose shone an infectious smile.

The computer completed its clunking start-up and the palmist opened Myanmar Traditional Astrology, a programme with a grey interface that produced various graphs based on the date and time of my birth.

“Hmm.” He rested his elbow on the desk and his chin in his palm. “Your symbol is a set of scales, which means you’re a balanced person: you stick to the straight and narrow and dislike violence.” He studied the graphs and diagrams for another minute, occasionally nodding, then looked round at me and beamed.

“Okay, place your hand here.” He produced a clean red cushion and rested it on his lap. I lay my right hand down and the palmist began his inspection.

“You don’t believe in palmistry at all,” he said instantly, still smiling. I muttered something about it being uncommon in England and he returned his attention to my hand.

“You’re writing a book.” I nodded. Shwe Ei gave me a nervous smile. “And you hate imagination.” Well that didn’t bode well for my fantasy novel. “You’re Protestant.” “No.” “Catholic.” “No.”

“Presbyterian.” “Actually, I’m not religious. But I am interested in Buddhism.” “Hmm.” He traced an arcing line in my palm with his index finger. “This is your life line. It’s long: you’ll lead a prosperous life with no major incidents – but only if you pray. Avoid prostitutes and KTV girls.”

Shwe Ei raised one eyebrow. “You’ll be successful in education – maybe you’ll publish educational books – and will be loved by... hmm. Kalar-go Ingaleik-lo be-lo pyaw-le?” he asked Shwe Ei.

She shifted uncomfortably. “‘Kalar’ is used for anyone with darker skin than, you know, a Bamar,” she said to me. “Normally it means Muslims and Hindus.”

“Yes, you will be loved by the kalar community,” said the palmist with a nod. Intriguing. “Do you have any specific questions?” he asked, looking from me to Shwe Ei and back again.

I had so many questions. “Could you tell me about my next two years, please?” He beamed and took my palm. “You’ll come into lots of money through fortune – you have a good chance of winning the lottery, though I can’t say in which country.”

Shwe Ei giggled and clasped my left hand. “And you’ll meet your future wife while travelling. She’ll be of a different nationality and religion to you.”

Shwe Ei let go of my hand and folded her arms. “All your relationships until now have meant nothing to you. I’m right, yes?” And he smiled as never before, hla-de but haunting.

“Err...” I glanced at Shwe Ei, who was now staring at the wall with her back turned. We had been together six months, but I would start travelling round Myanmar next week – and that would signal the end of our relationship. We had agreed this before officially becoming a couple. For several reasons, including visa complications and personal ambitions, neither of us could see a long-distance relationship working. Our time together had been incredible, but now that we were soon to part, emotions were running high; Shwe Ei in particular was finding things difficult.

“You’ll also live in India for two or three years,” continued the palmist, his smile once again revealing a set of flawless teeth.

It was time to leave. After a quick selfie – which the palmist later uploaded to his Facebook business page – Shwe Ei and I thanked him and left. The downpour had ended, and the clouds had cleared, allowing the scorching midday sun to take control. We wandered over the puddled lan and out the pagoda complex, at which point I assured Shwe Ei that our relationship had not been a mere fling and that she did, in fact, mean a lot to me.

“I went to him before we met,” she said, turning soft, unreadable eyes to me, “and he told me that I would ‘meet a foreigner.’”

I clasped her hand as my heart sank. Now I knew why she had been finding the imminent split more difficult than me: she believed our coming together had been determined by fate, but she hadn’t known I was destined to leave.

Shwe Ei isn’t the only Myanmar that believes in astrology, palmistry, numerology and fortune-telling (which I will refer to collectively as “astrology” from now on, since Myanmar astrologers usually employ a combination of these practices). Most Myanmar are superstitious, and astrologers are highly respected. Their main clientele are women aged twenty-thirty seeking counsel in love, but people may ask their advice on almost any topic, including life changes and business deals.

The recently deceased ET – Myanmar’s most renowned astrologer, named after her resemblance to the Hollywood alien – charged $1000 per hour and her waiting list was reputedly a year long. Her party tricks included telling the serial number of a bank note in a person’s wallet. One of her clients was former leader General Than Shwe, who in 2005 moved the country’s capital from Yangon to Naypidaw; many believe he did so on the advice of an astrologer.

Astrology and superstition played an influential role in Myanmar politics for many years. Myanmar signed its declaration of independence from the British on 4th January 1948 at 4:20am – a date and time chosen by Myanmar astrologers because it was deemed auspicious. And in 1987, former dictator Ne Win reformed the Myanmar currency by printing new notes divisible by nine, his lucky number. Some 75% of the old notes became worthless overnight and no compensation was given for them. Millions went bankrupt.

Fortunately, the change to a democratic government means that military generals can no longer make such devastating political decisions on superstitious whims.

*

I had moved to Yangon nine months previously to work as a teaching assistant at an international school. When my friend told me about the job, I had just returned from a disastrous trip round Croatia and Slovenia, so the idea of shooting off abroad didn’t initially appeal. Besides, I had never been to Myanmar and frankly knew little about the place.

After just a day of research, however, a burgeoning curiosity emerged for this country, which had undergone such turmoil over the past few decades and which now appeared to be entering a new epoch.

Following a successful Skype interview, I accepted the offer and was ready to leave England a week later. With only one minor hiccup, when the employee at check-in needed convincing that Myanmar was a real country and that Emirates flew there, I was on my way.

My time in Yangon was enjoyable overall but not especially enriching. Everyone had told me that I would have an incredible cultural experience, but I had spent most of my year walking past Insein Road’s countless mobile phone shops, staring at adverts reading “perfect selfie”, “selfie king” or “selfie master” (a phone’s chief selling point being the quality of its front camera), and teaching phonics to elite Myanmar toddlers, one of whom was so famous that he had a Facebook fan page with literally hundreds of thousands of followers. I was trapped in the big city bubble, detached from what was going on elsewhere in “Burma” – as many people still called the country. I knew, however, that Myanmar had to be out there somewhere – be it maiden, monster, or misunderstood – and I was determined to “find” it.

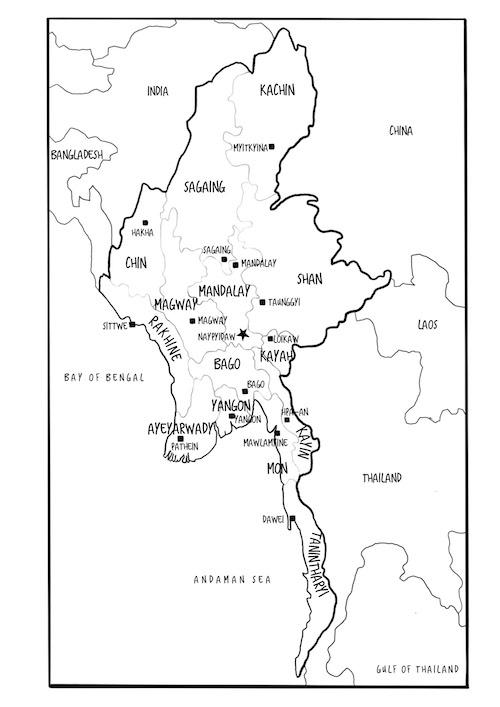

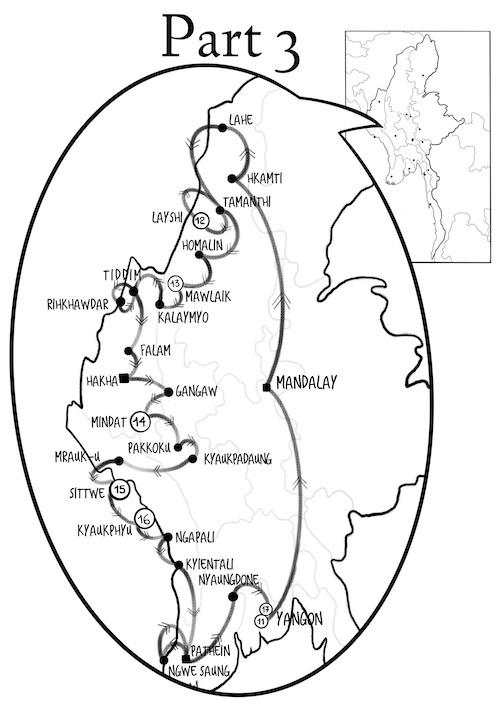

So I began plotting an expedition round the country, hungry for knowledge and experience. To realise my aim of “finding” Myanmar, a nation roughly the size of France and home to over 100 ethnolinguistic groups, I resolved to talk to people from all walks of life and to explore a wide range of landscapes and cultures. This would involve travelling to every official Myanmar state, particularly to regions recently opened to foreigners. Only then, I felt, could I begin to fathom what was really going on in this reputedly fascinating, diverse and turbulent country.

In preparation for my trip, I spent the final few months of my contract devouring books and catapulting myself into learning the language. I had studied Ancient Greek, German and Latin at university, but Myanmar was a whole different ball game. I confused tones, battled with aspiration and spent days trying to decipher the script. After all, was there really any difference between ဘာ, သာ, ယာ, and ဟာ? (The answer is yes, a lot).

Each of my lunchbreaks was dedicated to grammar; the school nurse gave me writing lessons; and during playground duty – when I should really have been paying careful attention to the children – I revised vocabulary from my phone or practised speaking with the cleaners (it’s okay, I only ever lost one child).

Once I had exhausted every available language textbook, I switched to reading Myanmar children’s stories. Shwe Ei patiently prepared me for conversations with inquisitive monks, probing policemen, and bribeable immigration officers. Gradually, I made headway; and when a travel journalism job for a Yangon-based magazine presented itself, my Myanmar odyssey no longer seemed a fantastical dream but a genuine and alluring prospect.

The thought of leaving Shwe Ei brought me to tears a couple of times over my last few evenings in Yangon, allowing doubts to creep into my mind. But I had already delayed my departure by ten days because of dysentery; it was time to go. So, after an emotional final night with Shwe Ei, we took a taxi to Yangon’s central train station, an impressive colonial building coloured grey, green and gold, and passed through the entrance manned by a sleepy police officer sitting beneath a redundant COMPLAINTS sign. With just a few minutes to spare, I bought my ticket for 1950 kyats (£1.02) – which included life insurance of K1.61 (£0.001) – hugged my chit-thu goodbye and boarded the decrepit wooden train.

The carriage speakers were choking out Buddhist prayers while young female hawkers shouted out the prices of “pa-ye-thi” (’watermelon’), “lepet thoke” (‘tealeaf salad’) and “biyar” (you guessed it, ‘beer’). Their cheeks, cast in soft shadow by the circular food trays balanced on their heads, sparkled with pretty circles of thanaka – a golden paste made from ground bark and water, which the Myanmar use as sunscreen.

After a short delay, the train began to move. And as it clicked and clanked its way out of the station at a snail’s pace, I waved goodbye to Shwe Ei – who stood still on the platform, wearing an elegant black dress and a sad, loving smile.

A moment later she was gone.