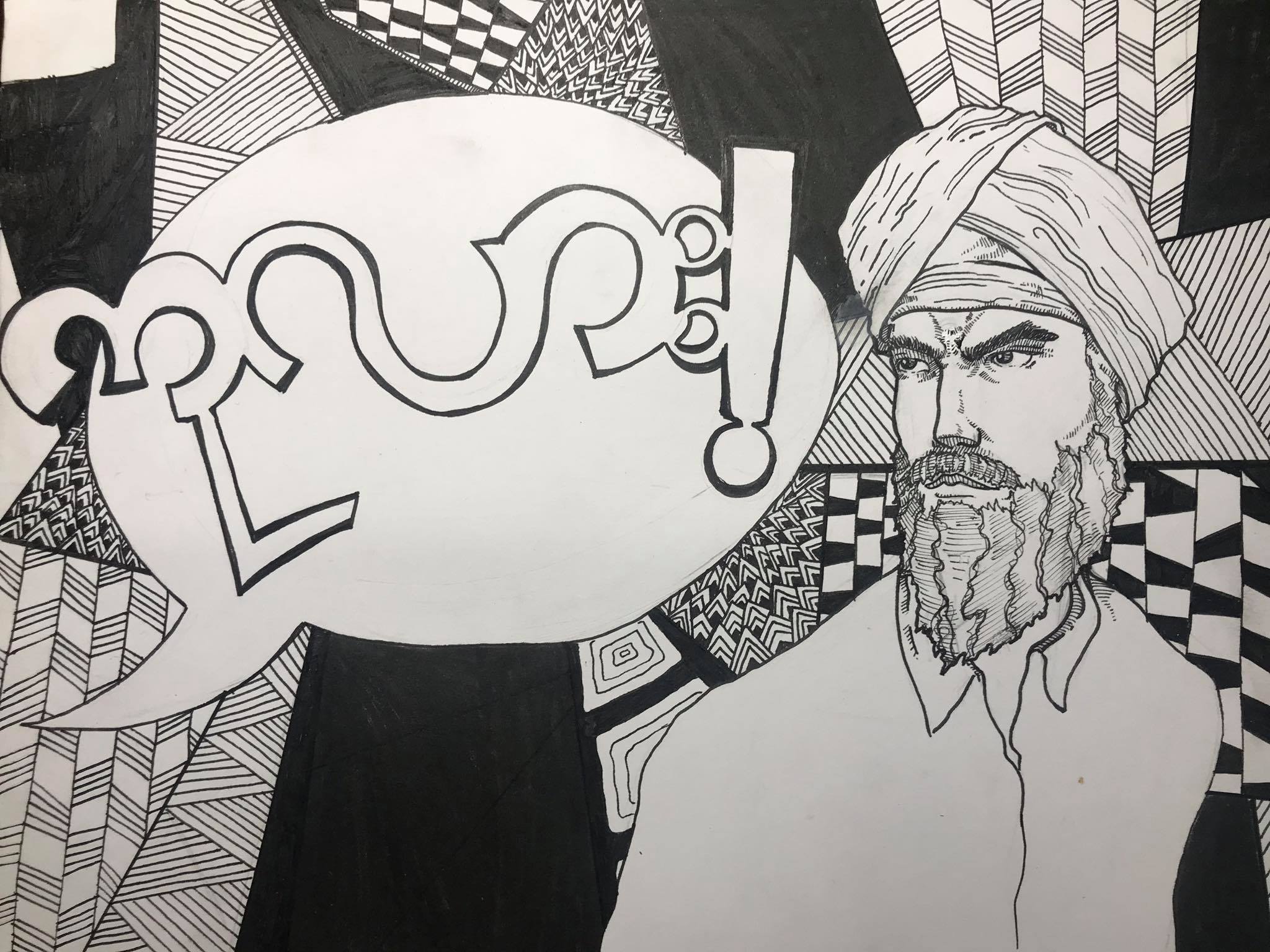

“Kalar.”

Once a seemingly innocent way to describe someone of Indian heritage, it has taken pride of place among the arsenal of racist vocabulary in Myanmar.

The word degrades, discriminates, and segregates people with darker skin, a broad-brush stroke of hate against those of Indian and Middle Eastern origin, and a contemptuous term used increasingly for Muslims.

Aung*, 20, was mistaken for an Indian Hindu growing up in Pabedan township—home to Yangon’s Indian quarter—and labelled kalar despite his mother being a Buddhist from Bangladesh, and his father a Sino-Burmese Sikh.

“You’re being categorized as someone you're not, and not in a very positive way,” said Aung, adding that the slur has connotations with “bad” and “disgusting.”

“I've seen people call my mother that word. At a young age, when I didn't know what it meant, it left a scar on me.”

When Kyaw Zin Soe, 20, has taken a taxi with his Hindu mother, more than once the driver has turned around and call them kalar.

“We tell them that the Buddha is also a kalar because he is from India,” he said. “Their faces get flushed and they get mad towards us for saying it.”

To rid the word of stigma, a change is needed in the way people see each other in Myanmar society, he said.

“Being politically correct is not a big thing in Burma and I feel like it should be if one is trying to achieve a holistic and non-hostile community.”

My own father is a 63-year-old third-generation Indian immigrant, born and raised in Sagaing region, while my mother is of Israeli descent, which makes me a “mix-blooded” Myanmar citizen.

This is another label that comes with its own set of problems, such as existing low on priority groups for government identification documents—and therefore waiting much longer for them.

My father was called kalar during his time in college and sometimes even now, while he runs our family business.

“People will assume that someone like us is just another Indian person who looks and talks the same,” he would tell me when I felt discouraged. “That’s why you should always improve yourself every chance you get.”

There have been times when I grew sick of the word and felt ashamed at my ethnicity. I was bullied during middle school, called a gorilla and kalar.

Although I think about the word in a different way now, I let it get to me back then. Perhap I was "kalar" and "gorilla" because I was too hairy, I thought, so I shaved off my arm hair (I sometimes wonder whether I’d be more or less hirsute now if I hadn’t done that).

But the word wasn’t always this toxic, says Kenneth Wong, 51, a Burmese language teacher at University of California, Berkeley. He cited a Pali-Burmese dictionary to explain its origin: “kula is defined as race, noble race, home, one's parents' home, or a patron feeding and taking care of one.”

The word was not derogatory, he said, comparing it to the semantic change of မိုက် mite, which originally meant “reckless” but in recent decades has taken on the meaning “cool.”

“Some people use it to refer to the Rohingyas, to suggest they’re not part of Myanmar,” Wong told me in a Facebook Messenger exchange. “This is different from referring to someone who has Indian ancestry, and may even choose to call themselves ကုလားလူမျို kalar lu myo (Indian people).”

Kalar is not necessarily equivalent to the n-word; consider the innocuous Burmese portmanteaus ကုလားထိုင် kalar htine (chair)၊ ကုလားပဲ kalar pel (chickpea)၊ သစ်ကုလားအုပ် thit kalar ote (giraffe) ၊ ဆေးကုလားမ say kalama (a sweet iced drink).

Facebook branded it hate speech in 2017, but the issue is more complicated, says Wong, who believes the intent behind the word’s usage is a deciding factor in its offensiveness.

“I’m Chinese and I’m not offended when people call me တရုတ် tayote (Chinese),” he said. "Some people use the word not to describe an Indian person but to call attention to someone’s dark skin. Some people use the word to suggest a person is a foreigner from Bangladesh. These types of usages are hurtful and derogatory.”

Like so many other problems in Myanmar, the sad trajectory of the word traces back to a lack of inclusivity.

Societal change takes time, but in recent years bursts of progress have been overwhelmed by a stalemate of intolerance. As development spreads wider from urban environments to the rural countryside, progressive ideas of a more just society—one against prejudice and with no limitations on any ethnicity or gender—may also take hold of the country too. But attacking people based on their appearance is attacking Myanmar as a whole—as long as we continue to do that, progress will remain an illusion.

Aung* asked for anonymity due to the sensitive nature of the topic.