An immersive experience in the late 1800s—say, the modern day equivalent of wearing 3D glasses in the cinema—involved staring through goggles at two identical images.

With our brain uniting the visual information from each photo, the images would blend together to create an illusion of depth, mimicking our visual system’s binocular effect.

Named stereoscopic photography, this technique whisked the observer away from their surroundings to faraway places they could barely imagine, let alone visit.

Around 1900, the pioneering stereoscopic company of the time, Underwood & Underwood, decided to give the world a glimpse of Myanmar (then Burma).

The result was 36 stereoscopic views captured across the country, one of a series of “stereoscopic tours” published as part of the Underwood Travel Library, which has now been digitized by the National Archives UK.

The prints are generally of high quality and some have detailed captions printed on the reserve.

They include towering images of Buddha, the rich mines of Mogok, pagoda spires and palm trees, fighters at a Buddhist funeral and the remarkable Gokteik Viaduct, spanning across a deep gorge.

Imagine what it would have been like, looking through a stereoscope and ‘touring’ a distant part of the world over a century ago.

A distant view of the Kyaikthanlan Pagoda, the town and the Salween or Thanlwin River at Moulmein (Mawlamyine), with palm trees and a temple bell in the foreground.

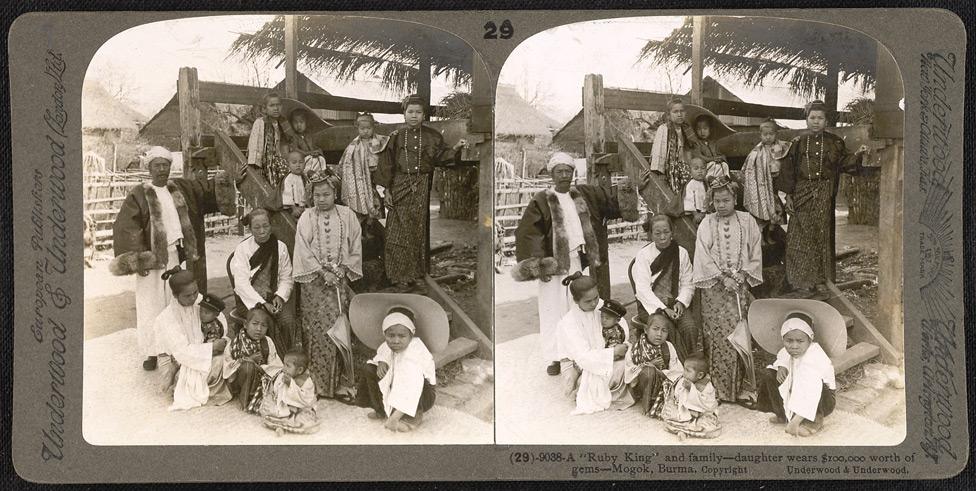

A Shan ruby trader and his family at Mogok. A caption printed on the reverse: “You find this oriental millionaire and his family outside their house, in the mining town where his fortune has been made. His strong, shrewd face certainly shows the ability which he must have exercised. That silken over-jacket is a garment corresponding in elegance to the sable-trimmed overcoat of a colder climate…All the family wear jewels to some extent; the young girl with the parasol is especially favored and wears (counting her ear-rings, bracelets and head-dress as well as her long necklace) fully $100,000 worth of precious stones, and she enjoys the fact just as any human girl would!”

A pause on the steep stairway up the side of the sacred Shwedagon Pagoda, Rangoon (Yangon).

A tamarind market at Pagan (Bagan). This view shows a crowd of people sitting on the ground with large baskets full of seed pods from the tamarind, a tropical evergreen tree, used in Burmese cuisine. In the background is a stupa and the tiered roofs and spires of a Buddhist temple or monastery.

The Shwesandaw Pagoda here is one of the country’s holiest sites. Legend recounts that the Buddha visited the area and prophesied the foundation of the nearby ancient Pyu capital of Sri Ksetra. This view from a hillside looks towards a picturesque cluster of pagoda spires amid palm trees and the Irrawaddy in the distance, with a group of Buddhist monks in the foreground.

A line of bells at a Buddhist temple in Prome (Pyay). The bells, used in Buddhist ritual, are hung on a sturdy wooden frame and are shown with monks standing alongside them. Behind rise the tiered roofs and spire of the pagoda, decorated with the ornate stucco and woodcarving traditionally found on monasteries and temples.

The interior of a Buddhist temple at Moulmein (Mawlamyine). This view shows a series of pillars inside the temple, richly decorated with gilding and mirrored glass mosaic. This form of ornamentation was traditionally used to create an effect of glittering splendour on the exterior and interior of sacred Burmese architecture such as pagodas, monasteries and palaces. In the foreground is a life-like statue carved in wood of one of the Four Sights - an old man, a sick man, a dead man and an ascetic - the sight of whom so moved the young prince Siddhartha that he resolved to devote his life to finding a means to ending human suffering, eventually attaining Enlightenment, and becoming known as the Buddha or Enlightened One. They were often recreated as life-sized statues and displayed in temples.

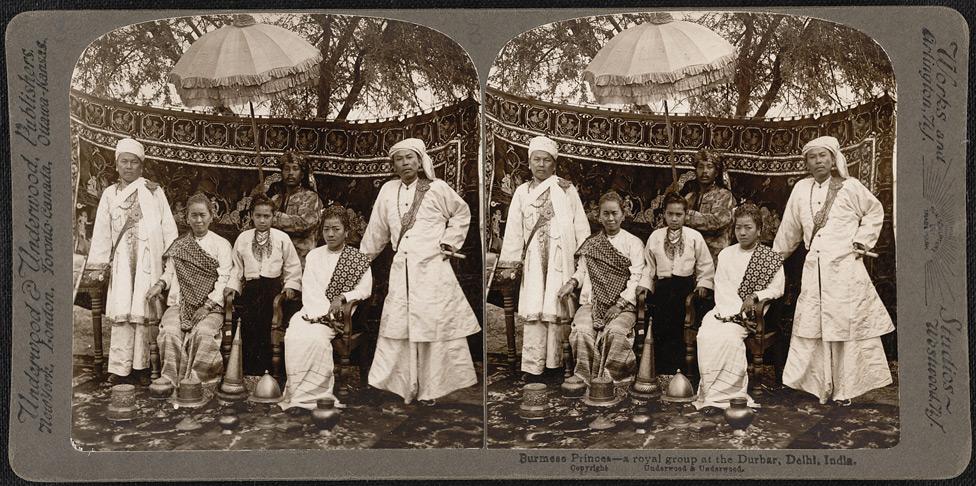

The photographs show two Shan rulers (sawbwas) standing with their wives seated between them, the group posed against an ornamental backdrop and shaded by a tiered royal umbrella, at the grand durbar in Delhi, India, in January, 1903, held in honour of the coronation of Edward VII.

A laung-zat (Burmese rice boat) on the Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) River. The laung-zat is an old vessel of the Irrawaddy used especially between Prome and Mandalay to transport rice down to Rangoon. This view shows the characteristic long, narrow hull, high-carved stern and bipod mast which carried enormous square sails.

A shrine in the Ngadatkyi Pagoda in Sagaing. The 17th century shrine is built in the form of a pyatthat or tiered wooden pavilion, a characteristic form of Burmese sacred architecture, and contains a giant statue of the seated Buddha. In this view his head can just be seen in the pagoda interior.

The photographs show porters on their errands and children at play in East Bazaar Road, Rangoon (Yangon).

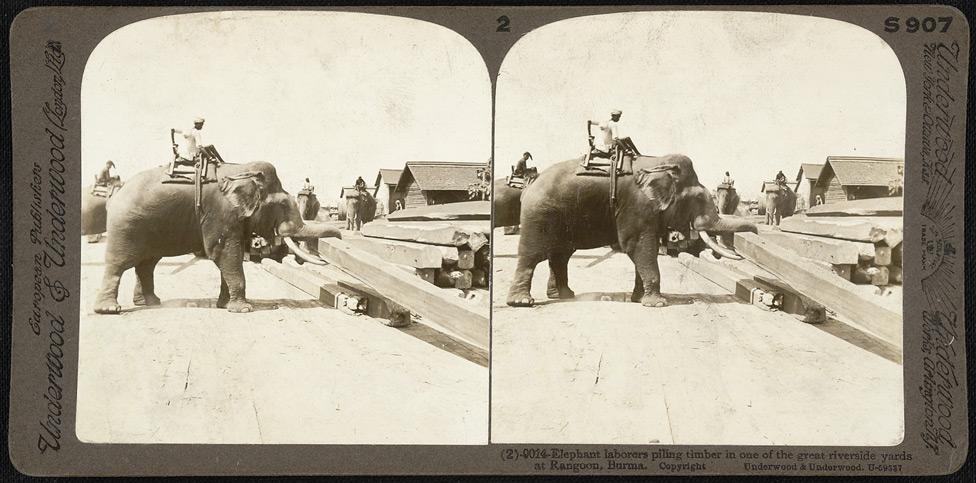

The photographs show an elephant in a Rangoon (Yangon) timber yard lifting a baulk of teak, described in a detailed caption printed on the reverse: “…We see at work piling the teak logs four of the nine elephants on the payroll of the lumber company. The beasts seem almost human in their actions. They work quietly, silently and deftly, sorting and piling the great logs. The rider, perched aloft on a seat like a sawbuck, seems almost superfluous. The foremost elephant was captured full-grown in the forests and trained to his task in a year’s time. The pair at the farther end of the yard work together. One inserts his tusks beneath the log, wraps his trunk about it and lifts it high enough for the other to slip his tusks beneath one end. Then together they lift the log and stalk softly to the pile with it. And no man could arrange a neater, more symmetrical pile…Small need has Burma of steam or electric power when such mighty and willing laborers as these elephants are at hand to do the work of its mammoth lumber yards. The forests of Burma are the finest in British India, and from them great quantities of teak, cutch, ironwood and India rubber are exported. Some of the great teakwood logs here came from beyond Bhama, 900 miles up the Irrawaddy.”

A Buddhist shrine in the Kelasa hills near Thaton in Mon State, Burma (Myanmar). The shrine is a small conical stupa built on top of a large “rocking” boulder poised on another outcrop of rock. This view shows a child posed in front of the boulder and a group of worshippers seated on the ground below.

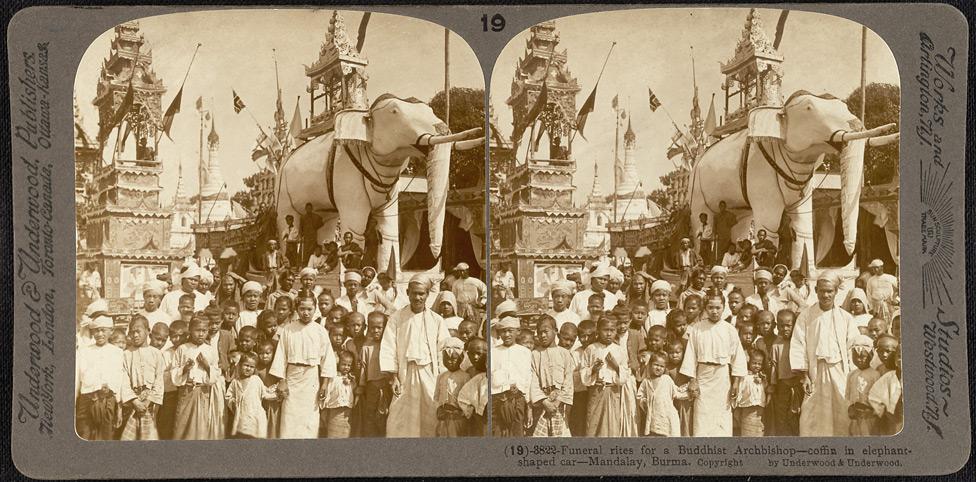

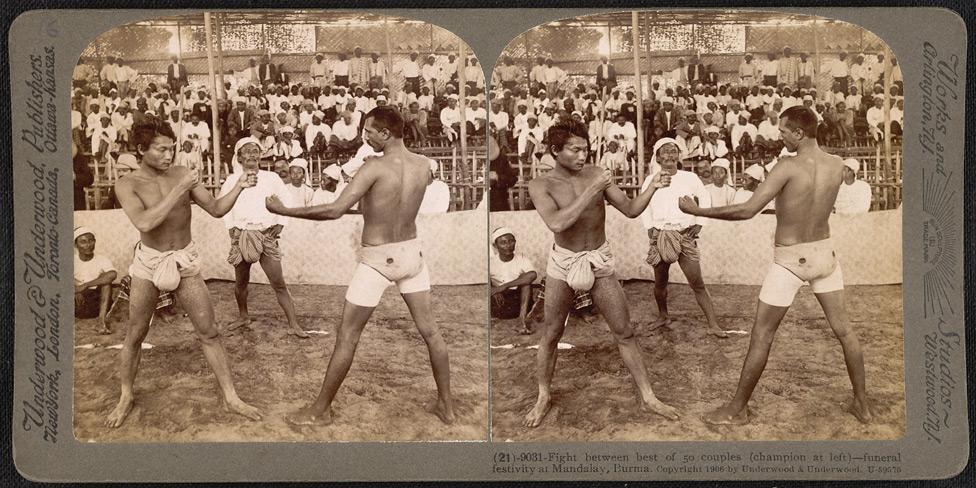

A boxing match held as part of the festivities of a Buddhist funeral at Mandalay in Burma (Myanmar). The prints show two boxers squaring off against each other, the muscular champion at left, with crowds on a grandstand and the referee in the background. The caption of another funeral image in the collection comments that: “This funeral is not a melancholy festival, for the Buddhist looks on death as a possible release from the cycle of soul migrations.”

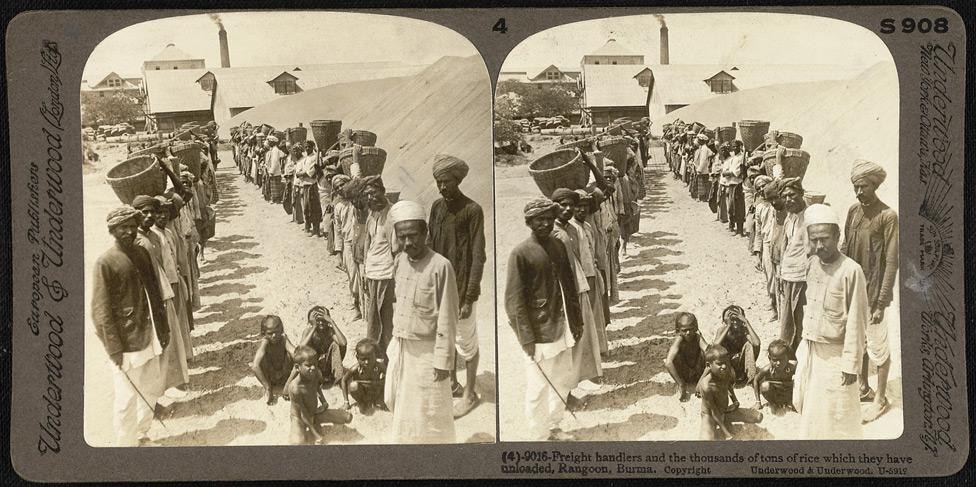

Freight handlers unloading rice at Rangoon (Yangon). The prints show two lines of labourers with their baskets, posed in the yard of a rice mill next to a hill of rice. A caption is printed on the reverse of the mount: “Look at the mountain of rice these petticoated Burmans have unloaded from freight steamers that have floated down the Irrawaddy, gathering in the crop from alluvial plains along the way! And this is but a fraction of the crop. Over 80% of the cultivated area is now given up to paddy culture. More than 2,000,000 tons of rice are exported in a season.”

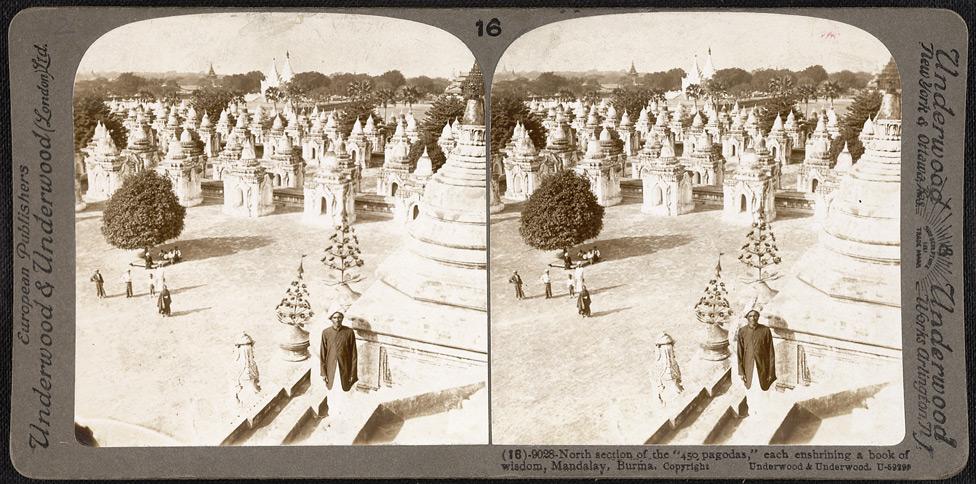

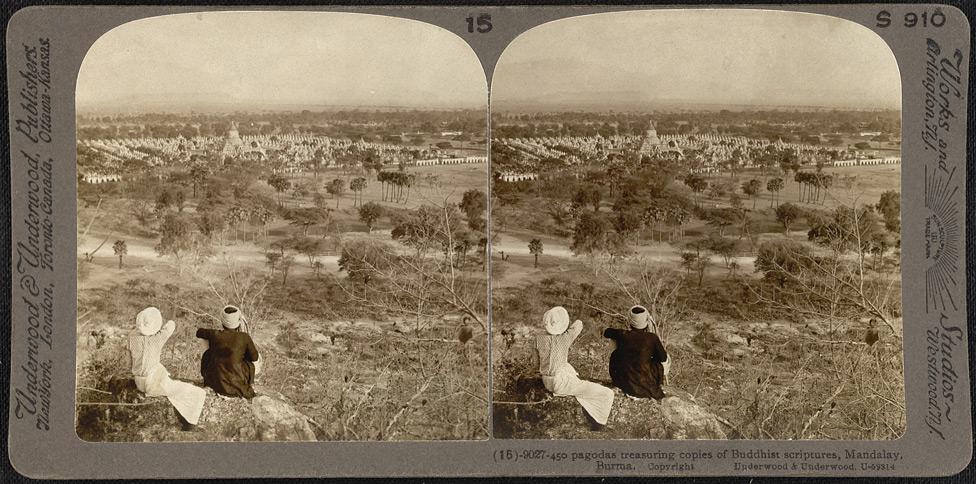

The Kuthodaw Pagoda in Mandalay. The central stupa is surrounded by 729 small shrines containing a marble block on which is carved in Pali script part of the sacred Theravada Buddhist texts. Taken as a whole they comprise the entire Pali canon or Tipitakas (Tripitakas in Sanskrit). A detailed descriptive caption is printed on the reverse of the mount: “Do you see what this slim Burmese maid in front of us is pointing out so eagerly down in Mandalay? It is the Temple of Seven Hundred Pagodas. In the midst is the usual bell-shaped structure, surrounded by seven hundred smaller shrines arranged in an immense square. Would you not like to see the treasured stone tablets in each of these shrines with their close carving of portions of the Burman’s Holy Book? The whole square, surrounded by a high wall, is a most impressive monument to the religion of Buddha.”

These prints show a view of the Shwedagon Pagoda; ornate shrines, a temple bell, and tall flagstaffs on the temple platform with palm trees in the background.

The viaduct carrying a railway line spanning the spectacular gorge at Gokteik in Burma (Myanmar). A caption printed on the reverse of the mount describes the gorge: “It is 180 miles eastward from Mandalay to Lashio, the capital of the northern Shan States…The backbone of the railway system of Burma is the line stretching from Rangoon to Mandalay and thence proceeding to Myitkyina, headquarters of the most northerly district of Upper Burma, 724 miles from Rangoon. But more celebrated is the branch that runs from Mandalay to Lashio, because of this bridge swung across the Gokteik Gorge. Along this ravine flows a rapid river which has eaten a tunnel through the rock barrier 400 feet high, directly in front of us. On either side are high bluffs of limestone, the one on the right, 1,000 feet high, is capped by tree-clad downs. The line is carried across the valley and gorge by a graceful trestle bridge to the bluffs beyond. It gradually ascends by a series of tunnelings and tortuous curves till it reaches the summit of the hills many feet above the level of the bridge itself. The abutments and foundations were prepared by the railroad company. An American firm of engineers erected the bridge, the total length of which is 2,260 feet. It is carried by fifteen lattice-work trestles, the highest of which is 320 feet long and rests upon the natural bridge of rock which spans the Chung-zaum river, 825 feet below rail level. 4,300 tons of iron and steel were used in construction, and 1,000,000 rivets. The cost was £113,200 ($566,000). These figures give some idea of the magnitude of the undertaking – here in the wildest surroundings of mountain and forest. Every pound of metal was shipped to Gokteik from New York, yet the work was completed in nine months.”

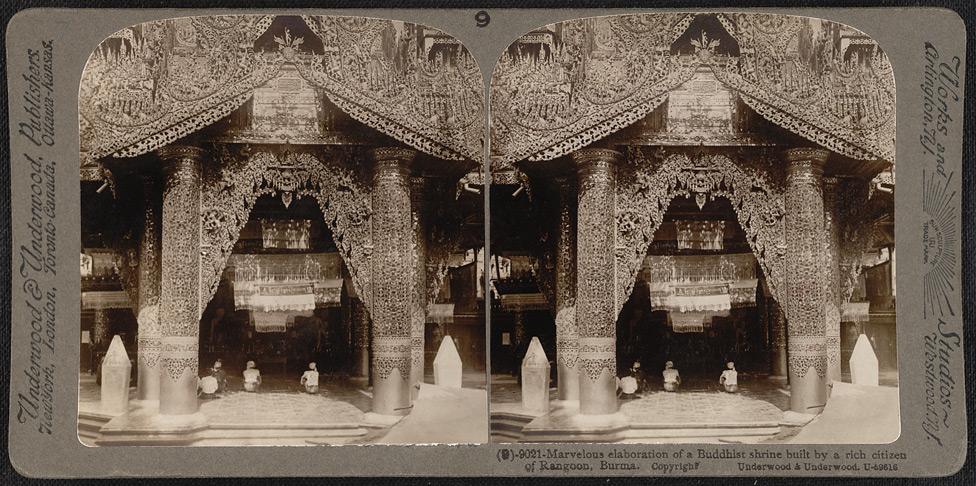

A Buddhist shrine in Rangoon (Yangon). These prints show offerings at the altar of a monumental Buddha sculpture, with children standing in a line before it, in a pavilion supported on massive columns.

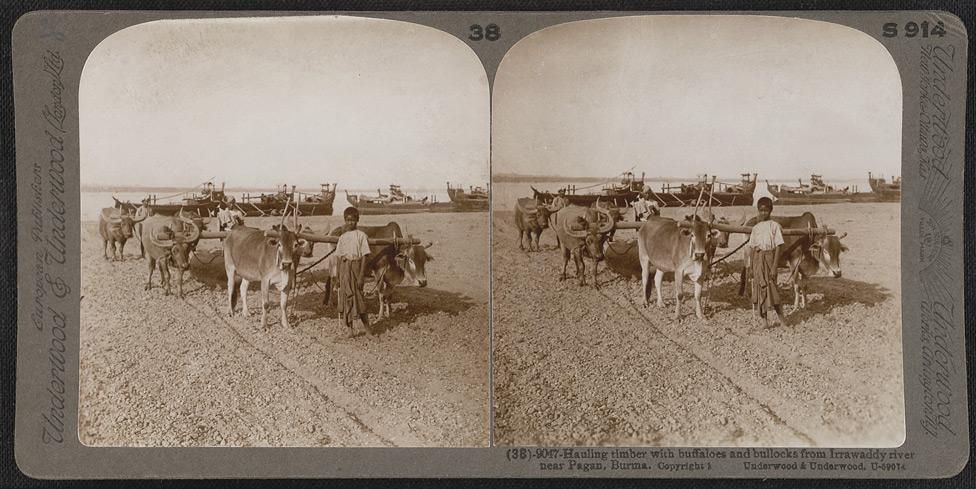

Teams of draught oxen hauling timber on the banks of the Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) River near Pagan (Bagan). This view shows the oxen in the foreground, with laung-zat, Burmese boats traditionally used to transport rice, moored beyond. A descriptive caption is printed on the reverse of the mount: “This log drawn by four buffaloes and two bullocks is a fair sample of the 200,000 tons of teakwood exported annually. Teak belongs to the government wherever found, and is handled only by the government agencies. Other valuable products are cutch, ironwood, India-rubber and the bamboo…The bullocks guarded by the petticoated Burman lad are of a type peculiar to Burma and parts of Indo-China. They are small, sturdy, docile, with only one hump and small horns. The buffaloes have the widely separated, spreading horns and narrow heads of the Indian buffalo. They are good workers but have an inconvenient fondness for the water which often impels them to rush to it, regardless of any burden they may be carrying.”

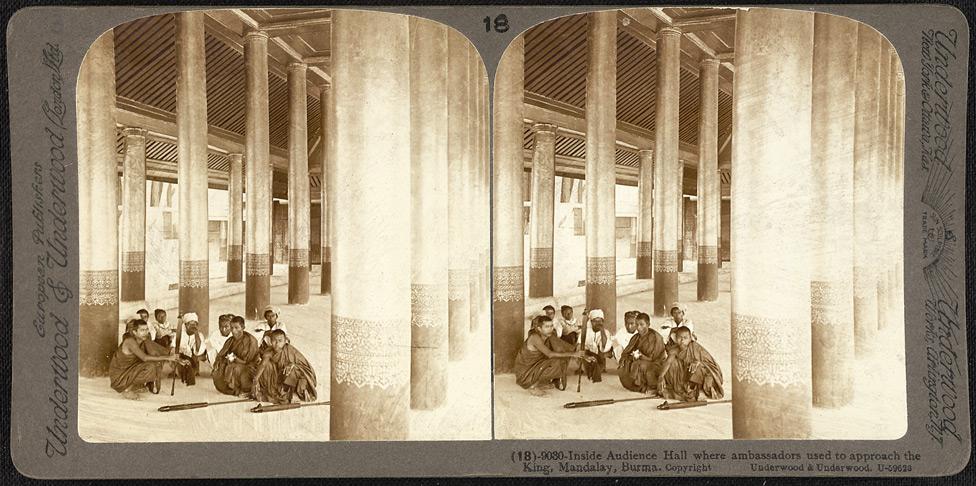

A view in the Great Audience Hall in the Nandaw (Royal Palace) in Mandalay. The palace was built by King Mindon Min (reigned 1853-78) when Mandalay was founded as the new royal capital in 1857, and stood at the centre of the walled city. It was one of the first buildings to be constructed and re-used many parts of the teak buildings from the old royal capital of Amarapura. These prints show a view of magnificent gilded pillars in the Great Audience Hall, which was situated at the eastern end of the palace facing the main city gate, with a group of monks crouched in the foreground. Along with the rest of the palace it was destroyed by fire during Allied bombing raids in 1945 during the Second World War but has since been reconstructed.

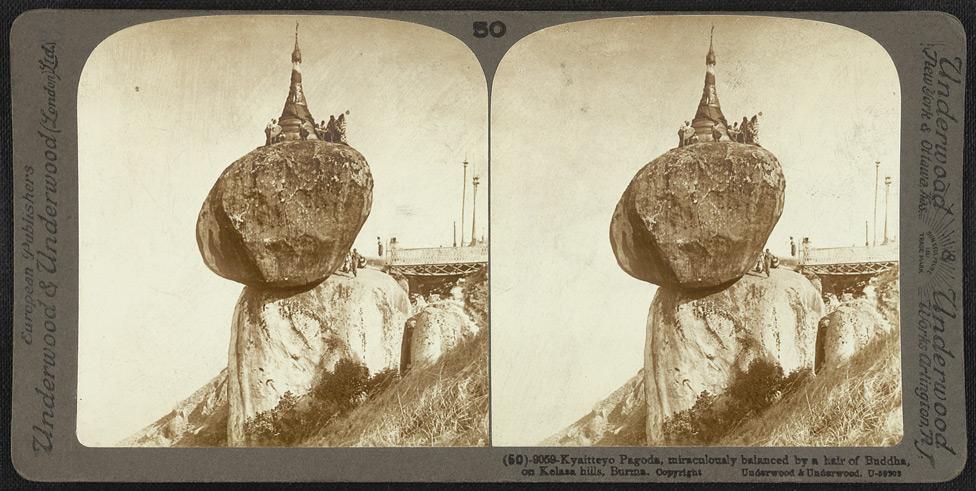

This is a general view of the “Golden Rock” pagoda, a stupa built on top of a massive boulder resting precariously on a hillside 20 kilometres from Kyaikto. It is said to enshrine a hair of the Buddha. The siting of this pagoda in the Kelasa hills near Thaton appears to be a confusion with print from the same collection, which shows a similar structure.

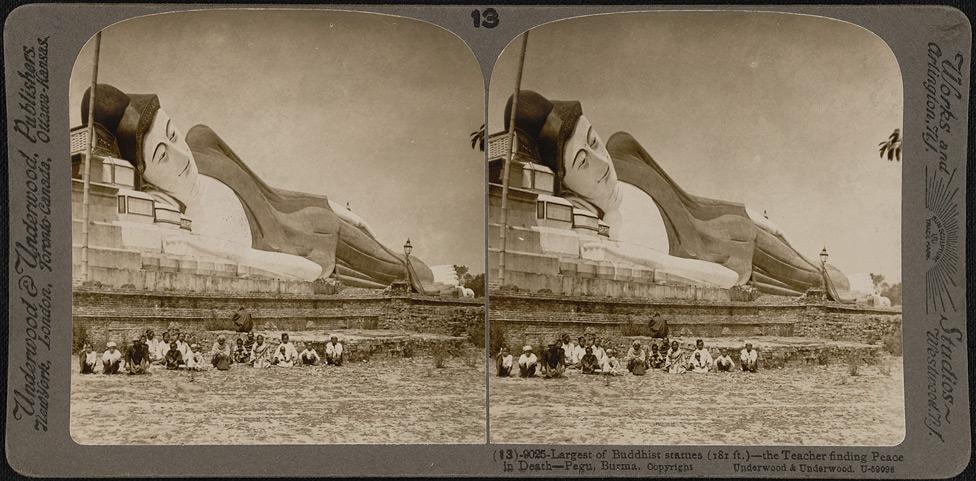

The Shwethalyaung Image, a monumental reclining Buddha sculpture, at Pegu (Bago). The Shwethalyaung image is the most venerated of the large-scale Buddha sculptures in Burma. It dates from 994 AD, in the reign of the Mon king Migadepa II, and is 55 metres (180 ft) long and 16 metres (52 ft) high. It had become lost after the destruction of Pegu in the 18th century, and overgrown with vegetation, but was rediscovered in the 19th century.

A shrine at Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon (Yangon). The Shwedagon is a gilded Buddhist stupa of legendary origins built on a hill and is the city’s most famous and revered monument. These prints show the façade of a shrine on the temple platform, which appears to be encrusted, so richly is it decorated with mirrored glass mosaic and woodcarving.

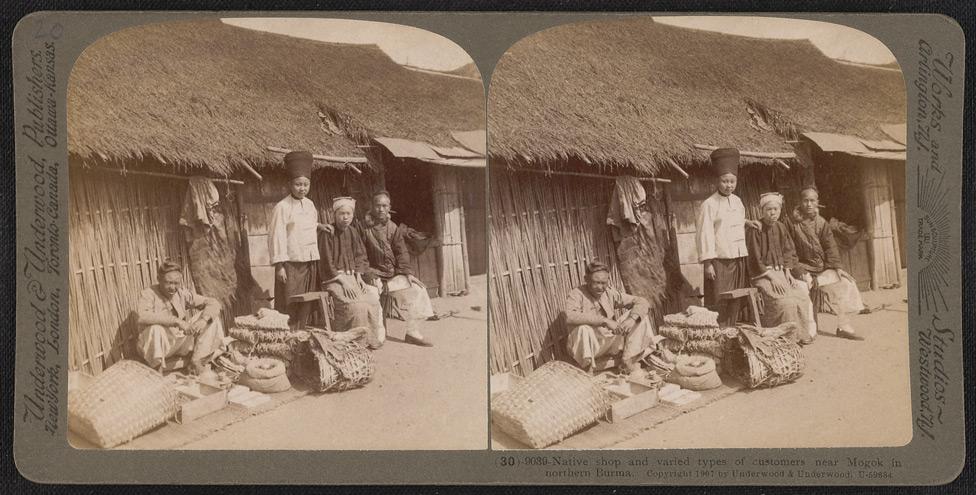

A street trader with his wares and customers near Mogok. They are shown outside a thatched building with walls of woven bamboo and represent different ethnic groups found in the important mining region of the Mogok Stone Tract in northern Burma.

These prints show a view from the Kuthodaw Pagoda central stupa at the base of Mandalay Hill of some of the 729 small shrines which surround it. Each one contains a marble block on which is carved in Pali script part of the sacred Theravada Buddhist texts. Taken as a whole they comprise the entire Pali canon or Tipitakas (Tripitakas in Sanskrit).

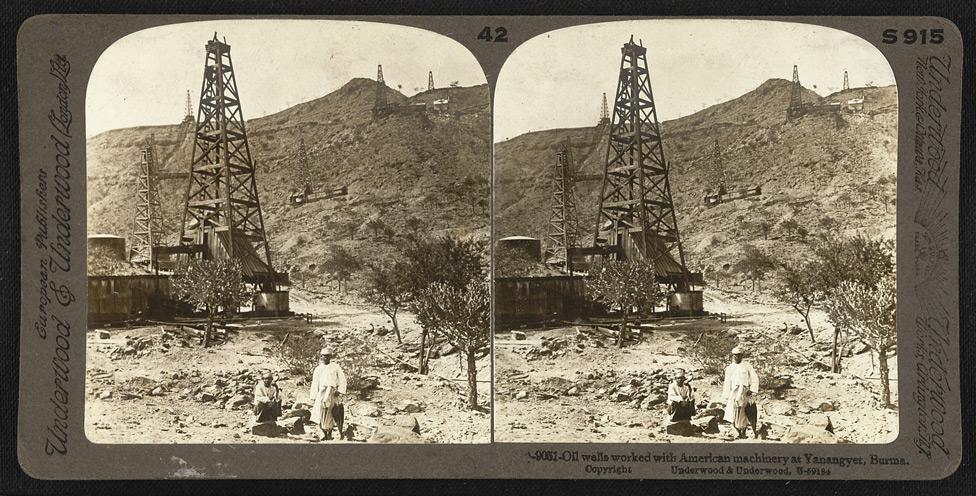

Drilling rigs on the oil fields at Yenangyat. Oil was the most valuable mineral product in Burma and the oil fields produced paraffin wax, illuminating oil and petrol for export. A caption printed on the reverse of the mount describes the scene: “We are at Yanangyet, 325 miles from Rangoon…You might think you were in southern Pennsylvania, for these derricks look just like what you would see there. And, in fact, these drilled wells are worked on the American or cable system with modern machinery. The richest oil-bearing tract of Burma is the Irrawaddy valley, which has three centres, Singu, Yenangyaung, and this field at Yanangyet. There appear to be no natural reservoirs filled with oil but it occurs in soft sandy banks from which it filtrates slowly into the wells sunk into the bed. These fields were worked by natives as early as the middle of the eighteenth century but modern appliances were not introduced till 1889. The Burma Oil Company carries on a series of regular borings. From the works the oil is piped to tanks on the river bank, whence it is pumped into specially constructed flats or tanks. These are towed by the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company steamers to Rangoon. The total production of oil in Burma is 85,000,000 gallons annually. A pipe line has recently been laid from this field and Sungu to Yenangyaung, 48 miles south. It is, in time, to be continued to Rangoon. This is a far cry from the day when native workmen dug wells and carried the oil in earthenware vessels to the river bank to be poured one by one into the holds of boats.”

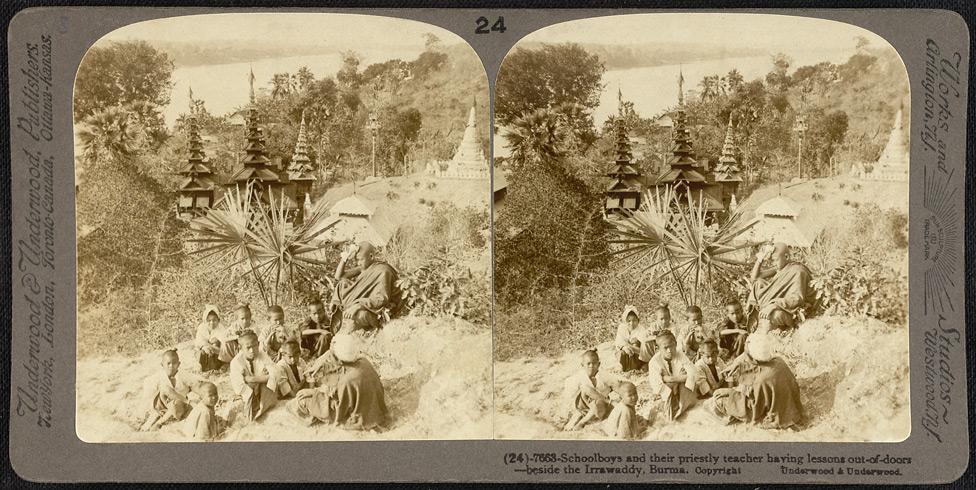

Schoolboys and their teacher, a Buddhist monk, beside the Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) River. The children are shown having an outdoor lesson, with the spires of a monastery or pagoda in the background and the river in the distance. In 19th-century Burma monasteries were the focal point of a community and traditionally also the centre of education until the British introduced a formal education system.

The prints taken in Mandalay show a coffin, enclosed in a tiered ceremonial bier, being pulled up a gangway to an ornate pyre, with mourners standing below. The caption of the image describes the pyre as a “gilded shrine” but this is unlikely. A detailed caption printed on the reverse of the mount describes the scene: “…the magnificent funeral car, with gaudy trappings and filmy umbrellas shielding the coffin from the sun, is being elevated to the gilded pagoda, while the by no means mournful throng below meditates upon the rewards of piety. And such a throng! Burmese sunsets are not more gorgeous than Burmese skirts of shimmering silk. Add to this color effect that of the ever present umbrella of light silk or orange paper and the many overpowering head-dresses of twisted silken scarfs, and you get the real charm of Mandalay.”

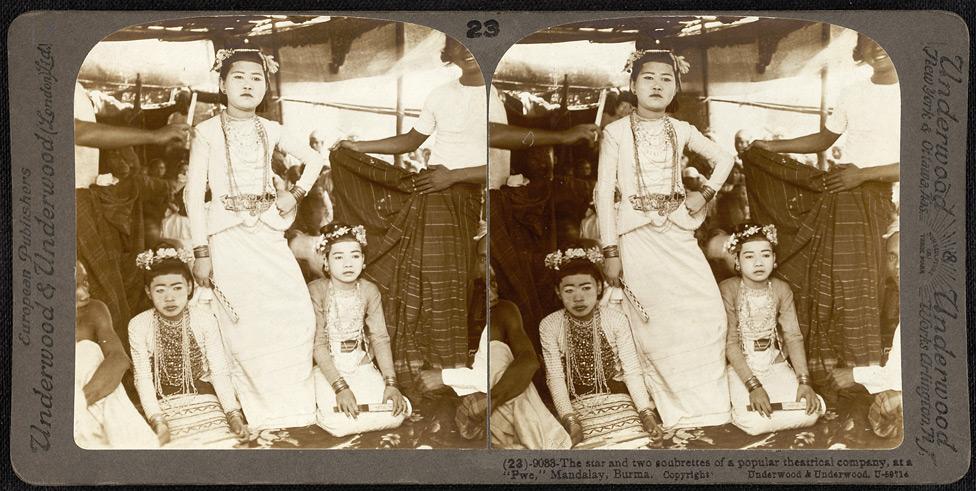

The star of a theatrical company and two supporting actresses in Mandalay. The three woman were photographed at a “pwe”, a popular form of Burmese dance performance, and are posed for the camera with the leading lady standing between the two kneeling girls. They wear elegant traditional costumes, jewel and flower headdresses, garlands of necklaces, and hold fans.

A timber raft on the Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) River. This view shows a group of people seated on the raft—their “floating home”—in front of a thatched shelter. This raft is composed of logs lashed together which may be being transported down river to a timber yard.

Seated statues of Buddha at the Kyaik Pun Pagoda in Pegu (Bago). The prints show two of the four colossal 30m-high Buddha sculptures which sit back-to-back facing the four points of the compass, built by King Dhammazedi in 1476. A detailed caption is printed on the reverse of the mount: “There are practically no archaeological or architectural remains in Burma except those associated with its religious history. Pegu has many pagodas and statues of Buddha but none is of more interest than this enormous Kyaikpun shrine. Do you understand that the four colossal seated figures, of which our present position gives us view of but two, represent the Burmans’ conception of the four great Buddhas of this world cycle? These figures, each ninety feet high and seated back to back, are beautifully polished and perfectly joined. They are in the usual cross-legged attitude, the sides of the feet turned upward. The palm of one hand hangs over the knee while the other is upturned. The face, rather flat with oblique dreamy eyes, is Chinese in effect. Do you see how the lobes of the ears are elongated till they rest upon the shoulder?...The scaffolding in evidence at the rear indicates that repairs are being made on one of the sacred statues…”

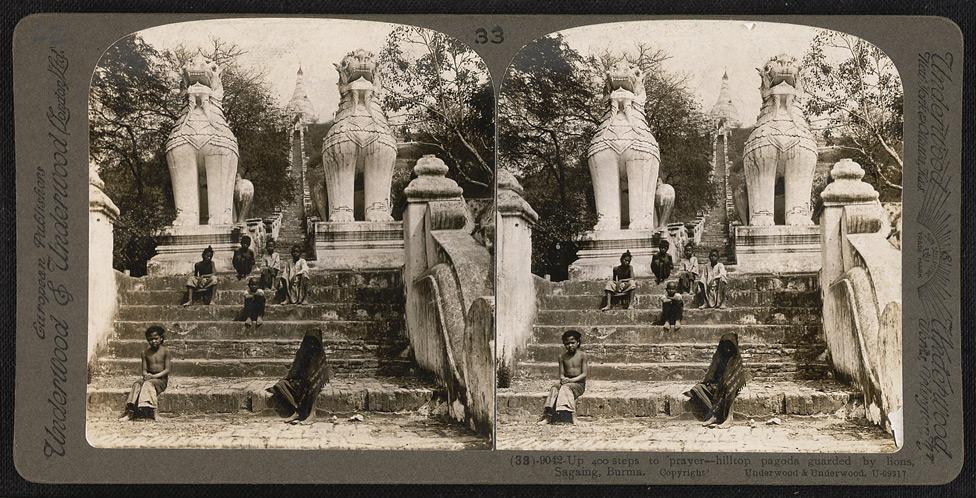

The entrance to a pagoda in Sagaing. The prints show a view up the long, steep flight of steps ascending the hill towards the Buddhist temple. Imposing statues of chinthes (mythical lions which are Burmese temple guardian figures) flank the stairway and children sit on the steps in the foreground.

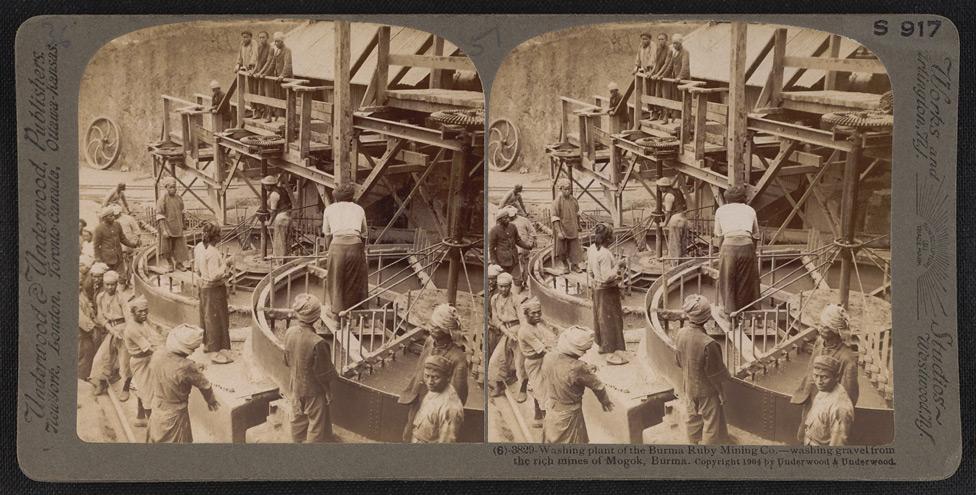

A view of gravel washing drums used by the Burma Ruby Mining Company in Mogok. A caption on the reverse of the mount describes the view: “This machinery is located, as you see, out of doors; you are in a valley among the tiger-haunted hills of northern Burma. These circular tanks, where mud is being churned by the revolving wheels, contain earth and gravel much like what you see in the bank yonder. As the horizontal wheel in the tank revolves, combing the mud with those vertical rods set in the spokes, the small stones that had been mixed with the mud separate themselves from it. Indeed there is a clever mechanical device that we cannot see here, which assorts the stones according to size. The stones are then dried and examined by experts to discover such rough rubies as may be mixed with the worthless waste. Unaccustomed eyes would be likely to pass over some of the most valuable gems. Garnets and sapphires (the ruby itself is practically a red sapphire) are also often found in the gravel…The managers of this washing mill are British, but the grimy workmen you see here now are chiefly up-country Burmese of various tribes. We are so near the frontier of China that a good many Chinese too drift into the valley, looking for employment and for possible fortunes.”

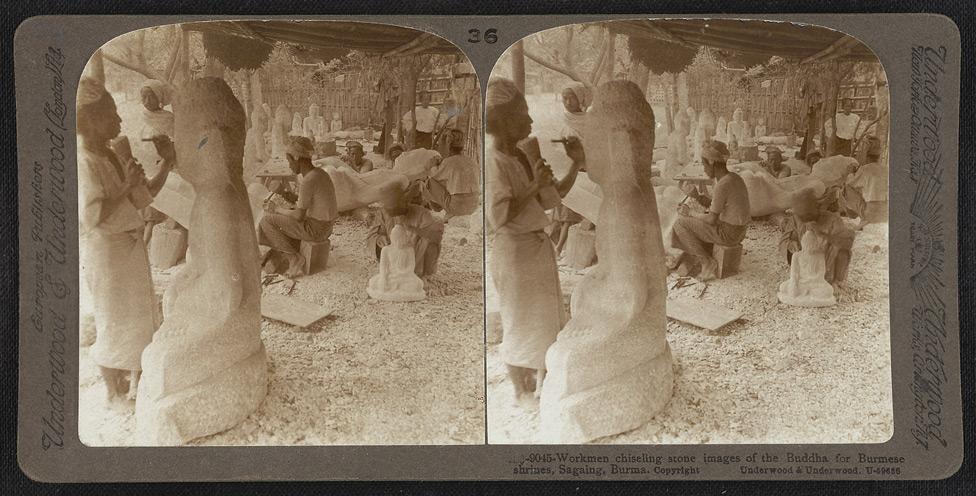

Artisans carving stone statues of seated Buddhas in Sagaing region.

![Gokteck [Gokteik] Gorge, the old haunt of jungle beasts, with railway 1000 ft overhead. Gokteck [Gokteik] Gorge, the old haunt of jungle beasts, with railway 1000 ft overhead.](https://myanmarmix.com/sites/myanmarmix.com/files/styles/collageformatter/public/collageformatter/media-img/976x495_copy_gokteck_gokteik_gorge_the_old_haunt_of_jungle_beasts_with_railway_1000_ft_overhead_north_burma.jpg?itok=49ieZ61b)